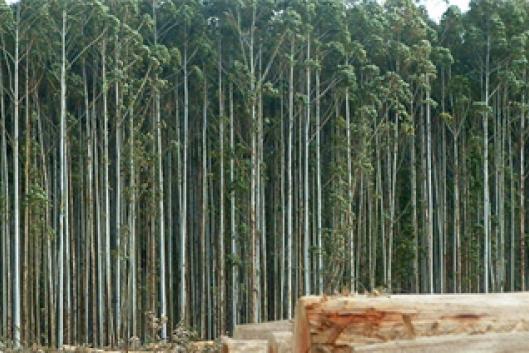

In the early 1990s, as a result of the Forests Law of 1987, the area covered by tree plantations in Uruguay began to grow rapidly, with rates of expansion sometimes greater than 50,000 hectares annually.

In the first years of the decade, transnational corporations did not yet occupy a predominant position in terms of the area of industrial tree plantations owned or managed, but two subsidiaries were created which quickly came to play a leading role: EUFORES S.A. and Forestal Oriental. The first was a subsidiary of the Spanish group ENCE, while the second was a consortium with two majority shareholders, the Dutch transnational Shell and the Finnish corporation UPM-Kymmene. Both began to rapidly plant eucalyptus in the western region of the country. Shell subsequently began to sell off its plantations to ENCE. The arrival of the Swedish-Finnish Stora Enso in the central region of the country in 1996 and U.S.-based Weyerhaeuser in the north in 1997 marked the beginning of the era of the transnationals, which have dominated the purchase of land for silviculture (*) in Uruguay ever since.

This period corresponds with the first phase of expansion of investment from countries of the North in the sector, which involved the expansion of tree plantations to supply raw materials for their industrial plants in Europe or North America. ENCE, for example, used Uruguayan wood to feed its pulp and paper mills in Spain. During the following period, the same companies sought to establish their pulp mills next to their new plantations in South America, as in the case of the ENCE and UPM pulp mills in Uruguay.

After the financial crisis of 2008, the period ended with only two pulp mill projects still active, those of UPM and ENCE. The latter was taken over by the Montes del Plata consortium, formed by Stora Enso and the Chilean group Arauco. In addition to the pulp mill, Montes del Plata also controls more than 270,000 hectares of land. The end result of this process was heavy concentration of ownership in the industrial tree plantation sector, with the gradual departure of smaller companies.

Leading companies in the industrial tree plantation sector in Uruguay as of 2011

|

Company

|

Country of ownership

|

Area of land owned (ha)

|

Area of tree plantations managed (ha)

|

| Montes del Plata (Stora Enso y Arauco) | Sweden, Finland, Chile | 270,000 | 156,500 |

| Forestal Oriental (UPM) | Finland | 231,500 | 151,000 |

| Global Forest Partners | Foreign | 140,595 | n/a |

| Weyerhaeuser | United States | 140,000 | 55,000 |

| Forestal Atlántico Sur | Chile, Uruguay | 75,000 | n/a |

| Grupo Forestal | Chile | 40,000 | 16,000 |

| Regions Timberland Group | United States, European countries | 32,500 | 20,150 |

| Phaunos Timber Fund | n/a | 31,500 | n/a |

| Cofusa | n/a | 30,000 | n/a |

| Caja de Profesionales Universitarios | Uruguay | 18,000 | n/a |

| Caja Bancaria | Uruguay | 18,000 | 7,739 |

| Caja Notarial | Uruguay | 12,748 | 9,102 |

| FYMNSA | Uruguay | 8,751 | n/a |

| Riermol | n/a | 8,610 | n/a |

| GMO Renewable Resources | n/a | n/a | 25,000 |

Note: n/a = data not available

Source: compiled by the study author

The presence of transnationals among the leading companies in the tree plantation sector means that the growing debate on the “foreignization” and concentration of land ownership in Uruguay inevitably involves them in this process. There is a clear process of concentration of land in the region, closely tied to the rise in prices of agricultural commodities and forest products in the first years of the 21st century.

It is important to distinguish between the concentration of land ownership and of tree plantations. In the region, when a company purchases land, there are rocky areas, streams, roads, stands of native forest, etc. which limit the establishment of plantations. In Uruguay, trees are planted on 61% percent of the landholdings on average. As a result, companies operating in Uruguay always own a much larger area of land than of plantations.

In addition to this necessary distinction between land and plantations, there is a second difficulty: some companies sign contracts with third parties in order to increase their area of cultivation. In some cases the company leases land from third parties on which it establishes plantations. In others, it provides the third parties with inputs and training so that they plant trees in accordance with standards of the company, which then purchases the wood when it is harvested.

Another difficulty arises if we want to move beyond quantifying the degree of concentration at the country level to analyse this phenomenon at the local level. Companies tend to only report total figures in regards to their assets, and only on rare occasions do they specify the exact location of their plantations and landholdings.

At the country level, the degree of concentration of ownership of industrial tree plantations is even greater than that of the extremely high concentration of agricultural land. In 2009, five agribusiness corporations operating in Uruguay accounted for “more than 20% of the land cultivated in the country,” with the distinction that most of this land is leased from third parties. In the meantime, in 2010, four companies controlled 31% of the country’s tree plantations, that is, almost 300,000 of the 950,000 hectares in total. Unlike the case in the agribusiness sector, these companies also own most of the land involved.

Measuring the percentage of the total area of plantations in a specific territory controlled by each company is a way of better understanding the hierarchies among the different actors in the sector. But that is not all: it also makes it possible to distinguish between situations where a single company dominates the activity and its local effects on the society (direct and indirect employment, stimulation of commercial activity, social impacts, etc.) and others where several companies are operating at the same time. In other words, it makes it possible to distinguish between areas that are highly dependent on a single economic actor and those with a lesser degree of dependence.

By even further refining the scale of analysis, we can see how some companies concentrate control over high percentages of the tree plantations at the local level. On the Uruguayan coast, the transnationals Forestal Oriental and Montes del Plata share the space and account for between 30% and 40% of plantations. In the rest of the country there are also high percentages of land concentration but to a lesser degree, with figures around 25% in the north and southwest. In southeast Uruguay there is a low degree of concentration due to the coexistence of numerous companies and a number of small and medium-sized plantation owners.

Levels of concentration above 20% denote areas where a very small number of companies dominate the industrial tree plantation sector, and thus enjoy a high degree of negotiating power with public authorities. It is in these regions that the issue of social dependence on these actors becomes significant.

(*) While they are often used interchangeably, the author has opted to use the term “silviculture” as opposed to “forestation” in order to more clearly reflect what companies in this sector do: they cultivate trees in the same way as agricultural crops are grown, waiting several years to harvest what they have planted, working the land and using agrochemical products. The term forestation, created by institutions that promote industrial tree plantations, such as FAO, tends to obscure the agricultural nature of this activity and fosters confusion between native forests and tree plantations, attributing environmentally beneficial qualities to plantations as if they were native ecosystems.

Sent by Grupo Guayubira, http//:www.guayubira.org.uy, e-mail: info@guayubira.org.uy, article extracted and adapted from “Forestación, territorio y ambiente. 25 años de silvicultura transnacional en Uruguay, Brasil y Argentina” (Forestation, territory and environment: 25 years of transnational silviculture in Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina), Pierre Gautreau, 2014, Editorial Trilce, Uruguay.