By Hendro Sangkoyo (1)

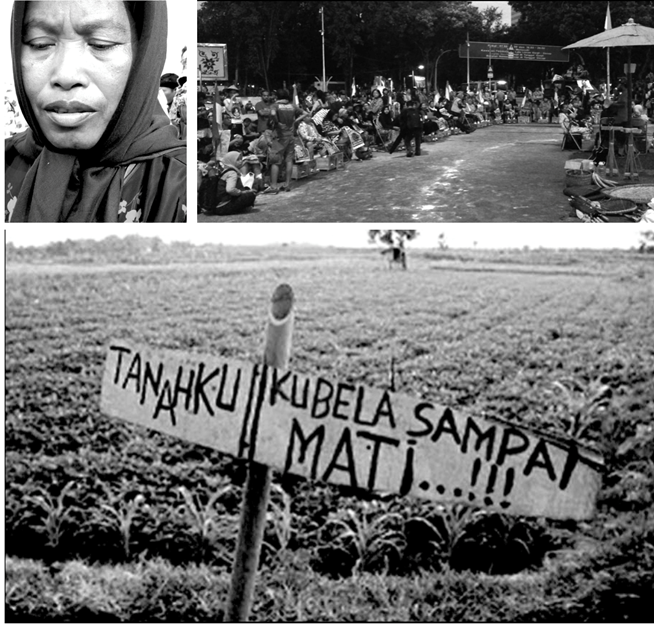

Patmi, 48, met her Maker very early morning on last Tuesday, the 21st of March 2017, during the short ride to St. Carolus hospital in Jakarta. Who she was most likely would have never came across the commercial media consumers in the country, if not for the politically peculiar circumstances of her death. As with hundreds of her fellow activist-landworkers who drove 538 km to the Capital from the Kendeng karst landscape, she had taken part in the sit-in protest just across the gate of the Presidential Palace. A week before, she requested the indulgence of her two kids and her husband to let her go. The pamitan (farewell) message, as recited by her daughter, sounded like coming from somebody embarking for the battlefield. "I am going to the Capital to defend (the fate of) my children and grandchildren." Flanked by her two sisters, Patmi and her company entered Jakarta in the black of the night, stole a few hours of nap and getting ready to cast her feet in concrete. Over the following six days and night she would sleep in the makeshift dorm that accommodated the growing number of protestors, being transported on a handcart back and fro between the sleeping hall and the restroom, and on daytime, endured the sit-in in the unpredictable weather of March.

On early Tuesday around three hours before dawn, while in the middle of getting prepared to return home with the rest of the group— a collective decision taken after a deadlock meeting earlier between four representatives of the protestors and the President's Chief of Staff, the drama evolved rapidly. She complained of nausea, soon developed a seizure and lost consciousness, before finally being rushed to the hospital.

How did Patmi herself give meaning to her action? Monday the 20th became the last day in Patmi's dignified and socially engaged life. In a chat with her on that day, her choice of words could not get any more pierceful: "What I want is... I wanted to speak to "pak" Djokowi; this problem must be resolved!"(2) This turned to be the political statement of her lifetime. She did not ask for help, assistance or mercy from the power-holder. She stated an emblematic demand, covering three presidential and two gubernatorial terms, encompassing at least five subprovincial districts overlapping the northern Kendeng karst landscape, and which has been voiced collectively in so many different ways. Her statement revealed what this sit-in is really about. For the sit-in company from Kendeng as it is for an ever-growing solidarity networks across the country, the second feet-cementing sit-in protest needs no sophisticated explanations. The demand has been crispy clear: Stop lifescape obliteration by the expansion of the cement industry throughout the Kendeng mountains! Ugly attempts at belittling the protest movement by isolating the spatial boundaries of protest, among other vices, failed to silence the resistance. In fact, Patmi's presence this time demonstrated her full support to fellow farming families in Rembang, about 40 kilometer away from her own community.

Over the past few years, those in support of the cement project, including those in charge of some key government agencies, the Governor of Central Java Province and the regional Police, a number of media conglomerates, a few academics and the emerging troops of social-media disinformation and propaganda professionals, have been having a field day nitpicking the communities' action, incriminizing them whenever possible, even messing around with the Supreme Court decision to revoke the environment permit for the project. Four days after Patmi's death, a major online media posted a spin-doctoring article urging the Police to investigate the possibility of a criminal or negligent act behind Patmi's death. The article should have asked the same regarding the rest of the forty-plus women and men. None of them thinks what they do is a picnic. It was tough. But in their own words, "this is nothing compared to what we may experience should the cement factory really operate."(3) Within a few days since the 21st of March, activists in Jakarta and other major cities in the country cast their feet in cement and staged similar sit-in, in solidarity with the Kendeng people.

How should we remember Patmi, her fight, her message and her death? In a local public outcry in 2013, the hamlets in the district of Tambakromo, Patmi's motherland, turned into a mesh of outdoor galleries of handmade posters against a second attempt at establishing a cement production complex there. A poster posted on a bamboo post in the cornfield provided an uncanny prescience of Patmi's last trip. "Tanahku. Kubela sampai mati" (My land. I defend (it) till death). Patmi returned home accomplished exactly that, leaving behind a haunting memory of sorrowful facial expression and a deep, peaceful gape.

Far beyond the immediate surroundings of the evolving drama, the Kendeng resistance against cement takes place in the face of the mounting pressure throughout Southeast Asia to escalate energy and material consumption, cement production included, in the wake of China's closure of 762 cement plants,(4) and to support the plans for inter-regional "corridorisation," by which both the mainland and the islands parts of Southeast Asia are subject to a massive land and water grab in the service of infrastructural development and a frenzy of extractivism. Such an unprecedented scenario will most likely cut deep into the remaining forests and other critical ecosystems in the region. In this light, Patmi's departure is surely going to haunt many generations of Indonesia's concerned citizens to come.

Rest In Peace, Patmi.

1 School of Democratic Economics.

2 Pers. comm., March 20, 2017.

3 Sukinah, Gunarto, "mbah" Darto, pers. comm. various dates, March 2017.

4 In Crackdown on Energy Use, China to Shut 2,000 Factories. TNYT, Aug.9, 2010.

From Top-Left, Clockwise: Patmi, March 20th, 2017. The Sit-In Across the Presidential Palace, Jakarta. A Protest Poster in Tambakromo, 2013.