The creation of “protected areas” throughout the world is mainly based on a philosophy that originated in the United States (US) in the late 1800s, which gave birth to a movement of national park establishment with the purpose of preserving areas of scenic beauty and natural wonders free from human intervention. This US vision of “wilderness” - which often ignored the critical role of native peoples in the management of landscape and has racist undercurrents - has been applied in many parts of the world, often with devastating effects on local populations living within forests. Despite these local realities, top-down “guns and guards” wildlife protection continues to be the norm, where large areas are set aside and local populations are prohibited access to and/or use of the natural resources they have long depended on. Conservation planning continues to be dominated by natural scientists and international conservation NGOs, often completely disregarding local histories, knowledge, livelihoods, and land and usufruct rights. There are numerous accounts from around the world of intolerant and coercive approaches of park managers towards indigenous peoples living within park areas.

Protected Areas in the Congo Basin

The area under Protected Areas status in the Congo Basin has increased considerably in the past decade and is set to continue increasing, as governments scramble to meet internationally set targets. Gabon and DRC, for instance, have integrated these targets into national policy, and in Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) the rainforest area under protection already exceeds the international goal of 17 per cent. However, this setting aside of huge areas for conservation in reality poses a direct threat to the traditional territories of indigenous and other forest-dependent communities and thus also to their main means of subsistence.

None of these countries effectively recognises community land ownership rights (although all of them recognise some kind of usage rights, but in practice these are very poorly enforced). Most Protected Areas in the Congo Basin are formally state owned, even if the actual management of them is almost entirely dependent on local communities and their customary practices. Designating spaces for conservation effectively entails some form of dispossession for the people who depend on those forests, the most common being displacements and outright evictions as well as restrictions to livelihoods and cultural activities.

From a political perspective, the creation of Protected Areas has been an instrument of territorial control which started in colonial times, when hunting areas were created for the benefit of elites. Local populations were either driven out or severely restricted in their use of these lands. This trend continued under national governments after independence, when many of these hunting areas were officially recognised as Protected Areas. Many of these areas are now designated as National Parks, thereby imposing restrictions in terms of access and resource use, while extremely few are community reserves or indigenous and community conserved areas.

Colonialism, donors and conservation NGOs

Governmental agencies in charge of Protected Areas depend heavily on international donors and big conservation organisations for strategic orientation, and technical inputs, not to mention funding. Two examples from DRC illustrate this point well. Virunga, Africa’s oldest national park, was established by the Belgian King in 1925 “largely from the tireless lobbying of an American biologist”, according to the park’s official website. The second is the proposed Lomami National Park, an area which is currently in the process of being classified, also as a result of successful lobbying by US scientists. The recent example of Lomami, which is similar to the way in which most Protected Areas were more recently designated in the region, shows the persistence of this basic setup: “western” conservationists playing a hugely influential role in bringing Protected Areas into being.

Although the United States and the European Union are the most important donors for conservation in the Congo Basin, there are other very relevant players, including Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI), which is pushing for the implementation of REDD+ programmes in the region, the German and French governments as well as the World Bank. International conservation NGOs are prominent recipients of these funds (beyond the funding that they acquire through other means, notably through individual and corporate sponsorship). The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) are by far the two organisations with the strongest presence in the region, although they are not the only ones. These NGOs have huge control over information flows and are able to influence the wider national and regional conservation strategies. Despite the hundreds of millions of US dollars allocated to conservation projects in the region in the past decade, there is still little evidence of tangible conservation achievements. Protected Areas are failing to reach their own conservation objectives, raising questions about the sustainability of the current conservation model in the region.

National governments and local NGOs have had a limited participation in designing and operating conservation projects controlled by large foreign conservation NGOs. Thus, involvement of local communities has been even more limited. Local communities around these areas are aware of their clout and their relationship with these actors is often characterised by mistrust and conflict. According to a testimony from an indigenous person in South Cameroon: “Dobi-dobi” [WWF] people have more money than anyone here. They work with all the local big people, the évolués [elites/wealthy], extractive industries, safaris and even with ministers in Yaoundé. And the whites are behind them, even the Prince of England (sic) and the World Bank.”

Protected areas and extractive industries

The conservation model co-exists with a development model based on resource extraction with clear devastating impacts. Conservation programmes have often been explicitly designed not to contest these extractive activities, – notably logging, mining and oil concessions and agro-industry, with increasing expanses of forest being converted into oil palm and rubber plantations.

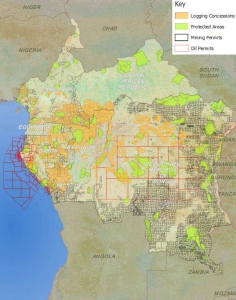

The study “Protected Areas in the Congo Basin: Failing both people and biodiversity?”, recently published by the Rainforest Foundation UK, shows how from the 34 Protected Areas examined in the region, more than half have mining concessions, close to half have oil concessions, and one reserve has three logging concessions within its boundaries.

Protected areas and extractive activities in the Congo Basin. Source: WRI/RFUK

Current approaches show significant shortcomings in tackling direct and indirect impacts of extractive activities bordering protected areas. For instance, migrant workers are commonly identified with significantly increased hunting and fishing pressure, and road building with increased illegal logging. Still, the most important international NGOs publicly defend their partnerships with corporations and rather than looking at this as a contradiction (as they also widely acknowledge their impacts), they portray it as a means to reach their own goals. Both WWF and WCS, for example, have “partnered” with some of the largest logging operations in the region.

What are the main problems that forest-dependent peoples and communities face when Protected Areas are set up in their territories?

Protected Areas threaten local livelihoods and wellbeing: Without exception, all communities where field research took place for the Rainforest Foundation UK study associate Protected Areas with increasing hardships. Diminished access to food (in severe cases even leading to malnutrition) as well as to forest products is directly affecting the wellbeing of local people. In no case has any compensation been given (or reported) for either displacements or loss of livelihoods.

Human rights disrespected in conservation initiatives: There is an enormous gap between the human rights obligations, principles and commitments of national governments, donors and NGOs, and what is taking place on the ground. There is consistent neglect and in some cases outright violation of instruments offering local and indigenous communities rights to lands, livelihoods, participation and consultation.

Conflicts and human rights abuses around Protected Areas are widespread: Communities around several Protected Areas throughout the region report abuse and other human rights violations, particularly at the hands of park rangers or “eco-guards”, besides the influence of an overarching trend of militarization in the region. The abuses are generally associated with aggressive anti-poaching, whereby local communities are targeted for hunting, although the impact of subsistence hunting is negligible comparted to hunting for domestic urban centres or international markets. Conflictual relations with eco-guards are not only related to the restrictions they impose, but to their often brutal behaviour towards local communities, including torture, cruel punishments, arbitrary detention and confiscation of property, forced entry, intimidation and rape. Accounts of abuses including physical violence and destruction of property have also been widespread in relation to evictions taking place when parks were created.

While local communities face severe restrictions on their livelihoods, extractive industries are tolerated: Whilst conservationists have tended to perceive local populations as the greatest immediate threat to Protected Areas, much more damaging large-scale extractive industries are widely tolerated by national governments and international conservation NGOs.

Indigenous peoples suffer disproportionately: Indigenous peoples appear to have suffered the most, probably due to their reliance on hunting and extent of their territories. The areas inhabited by indigenous peoples are often precisely those today perceived by foreign conservationists as holding greatest “biodiversity value”. This position of vulnerability means that they are also particularly exposed to the impacts of the conservation model. Most of the cases of displacement found for the study involved indigenous peoples.

Participation and consultation with local communities almost non-existent: In only about a third of the Protected Areas analysed in the study have local communities been consulted, and only a handful have involved them in management decisions. For the most part, the approach has predominantly been one of imposing strict top-down restrictions in terms of access to and use of forest resources, without integrating customary conservation practices or traditional knowledge. Large scale REDD+ projects are being planned in the Republic of Congo and in the DRC, which cover at least partially the Odzala-Kokoua National Park and the Tumba Lediima reserve, respectively. However, in both cases serious concerns have been raised that these plans are going forward without anything like adequate consultations with local communities and both apparently contain provisions that might actually end up dispossessing these peoples even further.

Conclusions

Conservation efforts in the Congo Basin are mostly failing to protect forests and biodiversity and are having serious negative impacts on local populations, and are therefore far from what could be considered just or sustainable. A fundamental shift is needed in the way in which conservation is conceived and practiced in the Congo Basin. Strong engagement with local peoples in securing their own capacity to conserve nature should be a priority. Local and indigenous communities in the Congo Basin have detailed ecological knowledge and traditional conservation practices, and strong links to the rainforest. Local governance institutions should be recognized as crucial, and the multiple ties that connect such institutions (i.e. livelihoods, culture, spirituality, identity) to their environments should be nourished, not dismissed.

Simon Counsell, simonc@rainforestuk.org and Aili Pyhälä, aili.pyhala@helsinki.fi

Rainforest Foundation UK, http://www.rainforestfoundationuk.org

This article is based on the report “Protected Areas in the Congo Basin: Failing both people and biodiversity?”, published by the Rainforest Foundation UK, which presents a study of 34 protected areas across Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Republic of Congo, assessing their impacts on people and biodiversity. For the full report, see: http://www.mappingforrights.org/files/38342-Rainforest-Foundation-Conservation-Study-Web-ready.pdf