In 1989, there was a war in the valley of Lila, Portugal. Hundreds of people gathered to destroy 200 hectares of eucalyptus, fearing that the trees would rob them of their water and bring fire.

On March 31, 1989, 800 people gathered in Veiga do Lila, a small village in Valpaços, and they led one of the largest environmental protests that has taken place in Portugal.

Seven or eight villages in a hidden transmontane valley had organized the action. Only later did ecologists join the cause. One afternoon, they all went to destroy 200 hectares of eucalyptus that a pulp company was planting on the Ermeiro farm, the largest agricultural property in the region.

The National Republican Guard (GNR, by its Portuguese acronym) was waiting for them. Two hundred police officers formed a first line of defense, aiming to impede the young trees from being torn out. But there were too few of them for such a large uprising.

The tension would escalate over the course of the afternoon. "For a moment I thought that things could be derailed," says António Morais today, one of the leaders of the protests. But the press was also present, and to this day, António believes this was the reason the violence did not escalate. There were some weapons—rocks on one side, batons on the other, but nothing that managed to silence the men and women, young and old people, calling out: "Yes to olive trees yes, No to eucalyptus!"

"We did not want to all burn here"

A couple months before the riot, António Morais, owner of several hectares of olive trees in Lila, noticed that a subsidiary company of Soporcel was preparing to replace 200 hectares of olive trees with eucalyptus for the paper industry. (1) "They had received a non-repayable grant from the State to reforest the valley [that is, a contribution with no obligation to pay it back], without even consulting the population," he continues indignantly, 28 years later.

"At that point, the Ministry of Agriculture fought tooth and nail to plant eucalyptus." Álvaro Barreto, owner of that portfolio, had been president of Soporcel's board of directors years before, and he would return to office in 1990, shortly after the people of Valpaços faced up to him.

"The prevailing thesis of the governments of Cavaco Silva was that it was urgent to replace smallholdings and subsistence agriculture with more profitable monocultures, that it was necessary to make forests profitable on a large scale," says António Morais. Eucalyptus promised an easy solution. Indeed, in a few years Portugal would gain a prominent role in the pulp industry.

"I began to read things and realized that eucalyptus would bring us major problems," continues António Morais. "For one, this is a region where water is anything but abundant, so we would have big problems with the viability of other crops—especially olive trees, which have always been this village's wealth. And then there were the fires, which were hell. Eucalyptus trees are highly flammable and reach a great height."

In the warm transmontane land, there are eight months of winter per year and four months of hell. The fire, he was sure, would come with those trees.

He began to talk about his fears with other people from the valley. "Slowly, a consensus began to build: that the easy profit from eucalyptus would be our downfall in the medium term. We did not want to let our land dry up. And we did not want to all burn up. We had to destroy that plantation, at any cost."

Anatomy of the Resistance

The nucleus consisted of a dozen and a half farmers who were able to mobilize the rest. "On Sundays we went to the villages, and when mass ended we explained to people what could happen to our land," recalls Natália Esteves—descendant of a family of large producers of olive oil—who was suddenly transformed into a leader of the protest. "And we also went door-to-door to inform people who had not been in the assemblies."

At first there were doubts, because the wood would always be worth more than olives, and chestnuts were not yet worth what they are today. "But we always tried to focus the conversation on what would happen within a few years, saying that the eucalyptus trees would dry up the land, people would be hostage to a single crop, and that if anything bad happened, they would be left with nothing."

What scared people most, however, was fire. "Where there is eucalyptus, everything burns. And so people no longer called these trees by their name, but called them matches."

At that time, João Sousa was president of the Veiga do Lila council. Today, at 86 years old and with the agility of a 30 year old, he quickens his pace to show the area that could have become a box of matches. "Look, there is not a single eucalyptus planted. And our valley has not burned in over 30 years."

The Portuguese forest tragedy of recent decades indicates that indeed, they were right many years ago, when the government and authorities told them otherwise. "We are people from the countryside, without education or knowledge, but we knew how to defend our land" says the old man.

The War

The people's first struggles to tear out the eucalyptus trees were clandestine, disorganized attacks. Two weeks before the war, on Palm Sunday, things intensified. "We gathered together two hundred people from the villages, and the company's owners called the GNR," recalls António Morais. "When they arrived we had already uprooted some 50 hectares of eucalyptus." That day people fled, but they warned that they would return after Easter.

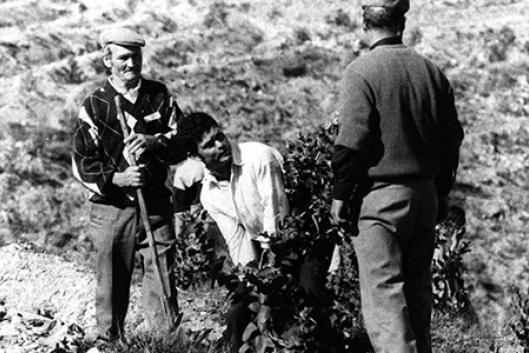

On March 31, 1989, the Sunday after Easter, the entire population would gather in Veiga do Lila to tear out what remained of the eucalyptus plantation. The village was packed with journalists, and there was even a helicopter covering the events from the air. It was not necessary to use shovels or hoes, given that the eucalyptus trees had been planted shortly before and could be pulled out by hand. The police tried to form a line of defense, but two hundred police officers were not enough for all those people.

In one hour, 180 hectares of small trees were uprooted. A dozen police officers rode out on horses in a show of strength, but it did not work. Soporcel had built terraces to plant the eucalyptus trees, and now the animals could not go down them.

All For One

The special police force was now advancing downhill with shields and helmets. José Oliveira, a farmer from the small village of Émeres, tried to escape off to one side, but was soon caught by the police. He had a revolver in his pocket, and that was what complicated the situation. "He was taken into custody and put in a van for illegal possession of a gun," tells his now widow, Ester.

That detention would mark the beginning of the end of the war. "People had retreated in the face of this intervening force, but when they realized that one of our people had been captured, they began to shout that they would not move until he was released," says António Morais. Ester says: "It was the whole valley that saved my man." Now they were not using rocks anymore, but shouts—to let Uncle Zé go free, and quickly.

A dozen protest organizers would be called to court, and one year later, they faced charges of invasion of private property and were convicted with a suspended sentence.

"Some engineers from Soporcel came to say that they would withdraw the complaint if we promised not to destroy a new eucalyptus plantation. I told them that that was unthinkable, that we would never have those trees in our valley." In the following nights, almost every remaining tree was covertly torn out.

Soporcel would end up giving up and selling the property.

Today, the Ermeiro farm is a land of walnut, almond, olive and pine trees. It has never burned. On that 31st of March 1989, the people united, and as they now say, they saved themselves. "We were right," they repeat again and again. They all repeat it.

This article is a summary of Ricardo J. Rodriguez's report, published in the magazine, "Noticias Magazine" in October 2017. Read the full text (in Portuguese) here: https://www.noticiasmagazine.pt/2017/valpacos-luta-eucaliptos/

(1) Soporcel merged with the company Portucel, to form the Portucel Soporcel Group, and later became part of the Portuguese paper manufacturing company, The Navigator Company.