The history of development is one of trickery and devastation, as it carries a manifold of (neo)colonial-loaded dimensions and abuses of extremely unequal power. WRM spoke with close allies from Brazil, Gabon, India, Mexico and Mozambique, to hear from them and learn about their understandings of development.

The history of development is one of trickery and devastation. Time and again, development financial institutions, banks and agencies—led by governments and companies in the global North—proclaim the ‘need’ to develop so-called poor (mostly resource-strategic) countries, in order to justify the introduction of large-scale infrastructure, extractivist projects and markets. Those impositions, they argue, would transform the countries into modern and developed societies. Meanwhile, most governments in southern countries are keen to receive what they consider to be much-needed additional funds and projects.

WRM spoke with close allies from Brazil, Gabon, India, Mexico and Mozambique, who have experienced the arrival of development projects in their particular contexts. We sought to hear from them and learn about their understandings of development. All names are kept anonymous for security reasons.

An activist from Santarém, in northern Brazil, asserts, “Throughout history, there has always been talk of development. But development here in the region is synonymous with capitalism, oppression.” For him, the opening of the BR-163 road, built with loans from the Inter-American Development Bank, is aimed primarily to allow soy and other commodities to be transported in a cheaper and faster way to the export port in Santarém, mostly with China and Europe as destinations. He said that “all of this happened with a large propaganda claiming that the region would develop, that the population would have more access to health, education and infrastructure—including in the rural areas—with a better quality of life, job creation, income and so on.” But none of this materialized. Meanwhile, the planned railway Ferrogrão (or Grainrail), which would run parallel to the BR-163, is heavily backed by commodity firms such as Cargill, Bunge and Amaggi; and it has financial backing from the Brazilian National Bank of Economic and Social Development (BNDES). The Kayapó Mekrãgnoti Indigenous People blockaded the BR-163 in August 2020 to resist the railway plans. (1)

Likewise, an activist from India told WRM that “The so-called Asian Highway, which is financed by the Asian Development Bank, is created by them and to serve themselves – survival of the rest will be defined by what is known as the ‘trickle down’ effect. It is about making roads that can bring the world’s resources to consumers’ doorsteps. It is increasingly about roads that local people cannot cross or use, but that move commodities faster around the world. People living on the side of the road who still practice Jhum (shifting) cultivation, who produce food for their family or village is thrown wide open to global competition. But it is evident that in a globalized world there is no competition, – you are already not in a position to fight. ‘Free’ trade is not possible in an unequal world.”

The term development has been a protagonist in the institutions driving and financing the transformation of vast territories and life spaces to the service of the market. This transformation involves countless community people being forced to enter the wage labour, in tandem with violent evictions, dispossessions, disruptions, assaults and injustices. This term –with all its associated connotations– creates a kind of consent, by making it seem like the goals and ideologies of powerful actors are the ‘common sense’ interests of whole societies. (2) As a result, those who oppose development are usually stigmatized with propaganda that claims they are either anti-development, disruptive of progress, backwards or going against the ‘national interest.’ The same activist from India continued: “Arguing against the highway is portrayed as anti-development or anti-people. There seems to be a pre-defined ‘development’ for which there are pre-defined institutions and policies packets as well as trained politicians implementing that ‘development’”.

While positioned as a neutral term, the notion of development carries a manifold of (neo)colonial-loaded dimensions and abuses of extremely unequal power relations.

The experience of women in Gabon living in and around Olam’s industrial oil palm plantations is a telling case. The African Development Bank (AfDB) financed Olam in 2017 for its plantations in Gabon, claiming that the funding is aligned with their initiatives, ‘Feed Africa’ and ‘Improving quality of life for Africans.’ (3) Yet, one woman from the village of Ferra told WRM that “since Olam came to the village, we can no longer fish properly because the lakes are polluted; some lakes and ponds are closed; we can no longer hunt because we have been prohibited from entering the forests.” Another woman from the same village said, “we are getting poorer, we are suffering, we are going through difficult times. Why do I say this?: The lakes are closed; the backwaters in which we used to fish are closed; now they are forbidding us from accessing the forests, and preventing us from planting as we did before. We are forced to use the same land several times, which unfortunately does not produce good crops. The best lands are for them and the bad ones are for us. We are hunted like animals; we became their slaves. They are the ones who rule over our forests and our village.” (4)

Countless large-scale dams, highways, trains, airports, industrial monoculture plantations, oil and gas extraction sites and pipelines, mines, mega-urbanization projects, etc. have been undertaken in the global South with the promise of development, growth, jobs and progress. Yet, the reality of those ‘receiving’ development has, for the most part, worsened.

An activist living in the province of Zambézia, Mozambique, who is affected by Portucel’s industrial tree plantations, told us—in regards to the promises the company made to the communities—that “none of that has happened. It promised to do many things, build schools, access roads, water pumps and hospitals, and nothing was built there. It also promised jobs. It said ‘you will work because we are going to make factories in Mozambique, in the province of Manica or Zambézia, and you are going to work.’ But all that is no longer said. There are only the plantations they have installed so far. People have stopped working. This is not development.”

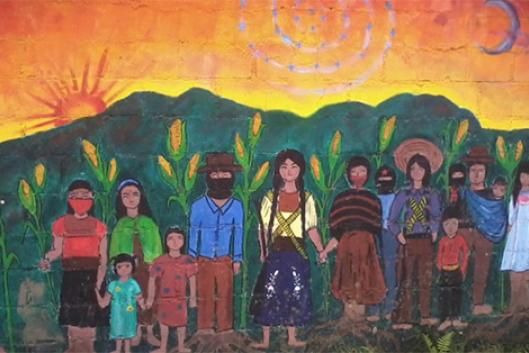

Likewise, a Mexican activist opposing the so-called ‘Maya Train’, which is backed up by the UN with the argument of “bringing development to the peninsula” and which will cross a vast territory where more than 3.5 million Indigenous Peoples live, demanded that promoters clarify whose development are they talking about. She said, “They are telling us that we are fools who know nothing; that we are ignorant; that we don’t know how to organize; that we don’t know how to collaborate in the development of our communities and our people; and that we don’t know how to work for the economic growth of our people. This is an insult to us. What development are these promoters talking about? What growth? Growth for them, for their companies, for businessmen, for those who have money? Because that is not development for the people! It is development for them. For us—the peoples and communities of the [Yucatan] peninsula—this will only bring negative impacts, such as division, more poverty, crimes, robberies, murder, prostitution, drug addiction. It will strip us of our language, our ways of speaking and dressing, and our forms of governance. They have come to destroy that. They bring destruction to the peninsula. We have our ways of living—belief systems we have had for many years, from our ancestors. We have our own life. That is what they have come to destroy. They are destroying the peninsula by destroying the life of indigenous and non-indigenous communities.”

The use—and imposition—of this misleading language, created by those with political and economic power, is extremely instrumental in pursuing the interests of governments and companies from the global North. It is also instrumental in covering up the implicit oppression, patriarchy and racism that lie behind such imposition.

The activist from Mexico continued: “They say that they are going to “integrate those who are not integrated.” They say, “you, peasant; you, indigenous person; you are going to be a partner because the Maya Train is going to pass through your territory, through your lands; and so you will be a partner.” That is a vile lie. It is a strategy to strip us of our lands, and to turn us into cheap labor to serve tourists. That is what they want from us. And what is really at stake is the destruction of the territory. Because that is what these businesspeople come to do, along with the Federal Government. They say they are reorganizing the peninsula. What are they going to reorganize? It is done! We have been taking care of the peninsula for centuries; our women ancestors took care of the jungle, and we continue to care for it. They are not coming to reorganize anything; on the contrary, they are coming to mess up what is already in place. So there is no development; there is no growth; there is no reorganization. That is all already done, because we have done it.” And she adds, “We naturally experience racism for simply having a different skin color or language; for the way we talk or dress; for the way we express ourselves; for the way we govern ourselves and our communities; for our traditions and culture. They discriminate against us because we are “Indians,” who don’t know anything. One way or another they disparage us. So in bringing the blessed development, they will also bring other kinds of people from other countries, because according to the government and the companies, they do know how to work. This is the racism we have experienced for many years, but now it will increase even more. They will tell us: “You are only good for serving tourists,” for working, for cleaning bathrooms, for mopping, for cooking, for selling our empanadas. That is how they will treat us. Because we are the people from below, from the communities, who do not know how to speak. That is how we experience racism, and it is going to increase more than it already is. We will be cheap manual labor through forced labor; we will be the slaves of businessmen, of companies, of this very government.”

An article from a 2014 WRM bulletin reflecting on the debates around ‘alternatives’ (5) clarified the real impacts of these development interventions: “In 1990, visiting European journalists asked Thai villagers who were trying to stop the Pak Mun dam what their alternative to the dam was. The villagers patiently replied that the “alternatives” were already there. We have our fisheries, they said. We have our community forests. We have our fields. We have our temples, our schools, our markets. These are what the dam would hurt or destroy. Sure we have problems, they continued. But we need to deal with them in our own way, and the dam would take away what we need in order to do that.” In this way, the alternative to development –which is usually presented as the only option for ‘helping’ communities in the South – is no development. Maybe this reflection can help to open up space for the many diverse realities and ‘alternatives’ to emerge, which still exist in many places—although they are largely being destroyed or weakened by development itself.

For the women in Gabon living in and around Olam’s oil palm plantations, alternatives to this imposed development must be theirs and not come from outside their villages. For them, “Our development is to have our own land and be able to live as we did before—from growing food, fishing and other rural activities.” And they continued, “[this would allow us] to develop our own projects to ensure our well-being in the village. This is what we want: to be allowed to go to our crops, to our forests so that we can be free in our village—a freedom we have lost since the arrival of Olam. It is essential that our land be returned to us.”. Fundamentally, they conclude, “we want freedom.”

* Many thanks to those who contributed and took the time to speak with WRM to make this article possible.

(1) Mongabay, Key Amazon grain route blocked by Indigenous protest over funding, Grainrail, 2020

(2) Ferguson J. and Lohmann L., The anti-politics machine: "development" and bureaucratic power in Lesotho, 1994

(3) AfDB, Loan for Olam Africa Investment, Program, 2017

(4) More information on the impacts of Olam’s operations in Gabon here.

(5) WRM Bulletin 209, An alternative to alternatives, 2014