Despite the massive clearing of mangroves to make way for shrimp farms, and the oppression of fishing and gathering communities, this industry has access to certifications that not only facilitate its entry into foreign markets; they also conceal a history of violence against the peoples of the mangroves.

Shrimp grown in captivity is considered to be a strategic product in the government of Ecuador’s national productivity plan. This industry was an illegal activity until 2008, when the government began a regularization process and basically handed over thousands of hectares of mangroves to shrimp entrepreneurs. This boost made it possible for industrial shrimp to be Ecuador’s second largest export in 2019, after oil.

The installation of large shrimp farms has been proven to cause profound destruction to mangrove forests, and to violate the rights of fishing and gathering communities in the mangrove estuaries. This includes violent displacement of these communities.

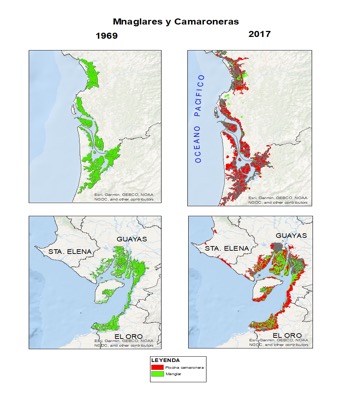

The National Coordinator for the Defense of the Mangrove Ecosystem (C-CONDEM, by its Spanish acronym), prepared a report in 2007 entitled Certifying Destruction, which denounces a series of violations upon which industrial shrimp aquaculture is based (1). The report details the destruction of mangroves due to the installation of shrimp ponds or farms between 1969 and 1999. By 2018, there were 1,481 shrimp companies, spread out over 230,000-260,000 hectares. The destruction continues to this day, and the dumping of polluted water has not stopped, according to testimonies from fishermen and gatherers of the mangrove estuaries obtained i

[caption id="attachment_22841" align="alignright" width="337"] Comparative map showing mangroves (green), and shrimp farms (red) in mangroves 1969/2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Aquaculture and Fisheries (MAGAP, by its Spanish acronym) / C-CONDEM[/caption]

Comparative map showing mangroves (green), and shrimp farms (red) in mangroves 1969/2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Aquaculture and Fisheries (MAGAP, by its Spanish acronym) / C-CONDEM[/caption]

n the Gulf of Guayas in 2019 and in Esmeraldas and Manabí provinces in 2020.

Since 2000, this industry has sought new market niches through organic certification programs, such as the German certifier, Naturland—which develops standards for organic shrimp slated for the European market. Despite the fact that shrimp farm installation is proven to destroy mangroves and violate the rights of fishing and gathering communities, organic producers were approved in Ecuador in 2002. Today, the industry has access to at least nine certifications that supposedly guarantee environmentally and socially “responsible” production.

The regulation of the shrimp industry: a death sentence for mangrove forests

Until 2008, the shrimp industry developed without permits for installation or operation; without any kind of leasing or ownership of the territories used; and without any kind of control of water usage and waste discharge. Furthermore, there was public recognition that this industry was established by destroying large areas of mangroves.

In 2008, then-Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa issued Executive Decree 1391 to “regularize” industrial shrimp aquaculture, on the grounds of regulating the activity and generating income for the State. Aggressive investment policies, huge economic incentives, and the certification of supposedly “sustainable” production boosted shrimp exports.

Thus, with the stroke of a pen, legislation that historically should have protected mangrove forests and communities’ rights was thrown out, and impunity was legalized. Regularization periods were extended by at least five years after the established time frame, and requirements were made more flexible, adapting to the demands of the sector.

Behind this regularization process, thousands of hectares of mangroves—which industrial shrimp farming companies had occupied illegally for several decades—were handed over to the same offending companies. This regularization also hides a long history of violations of communities in the mangroves. These violations continue to go unpunished and are even sanctioned, as the government promotes the image that this industry complies with environmental and social standards and contributes to the country’s economy.

Even the reforestation requirement, included in the Decree for companies to access the regularization process, is not being complied with. The Decree states that when a company occupies 1-10 hectares, it must reforest 10% with mangroves; for 11-50 hectares, 20%; and for 51-250 hectares, 30%.

Community members testified that the companies looked for places outside of the area of their ponds to carry out the alleged reforestation of mangrove forests. Some companies even bought areas of mangroves that communities had already reforested in the context of different projects.

In 2017, Ecuador passed the Organic Code of the Environment, which ratifies that mangroves are State assets; thus they are a common good, beyond any kind of ownership or appropriation. However, the Code leaves open the possibility for the fisheries authority to grant ‘concessions,’ which is how this territory has historically been privatized.

In 2019, Federico Koeller, a mangrove forest defender and activist from the Cerro Verde foundation in the city of Guayaquil, stated that the clearing of mangroves and the expansion of shrimp ponds had not ceased in the Gulf of Guayas: “...in recent years we have denounced the clearing of several mangroves within the Gulf, but there is no response from the authorities (...) The authorities carry out inspections alongside organizations, but there has never been a report, much less a penalty.” Fishing and gathering communities are driven away by an underhanded system of fear, which tries to incriminate them, or at least insinuate that they are suspected of robberies at shrimp farms.

Shrimp ponds in the Gulf of Guayas have armed guards, hired through security companies. In 2012, permits were issued for the shrimp aquaculture sector to carry firearms, “as part of the security plan to prevent robberies and attacks,” officials said. In this context, gatherers and fishermen face a more violent situation. In 2019, speaking of the shrimp companies, community members in the gulf said: “Now they think they own the mangroves; they show us papers which they say are property titles. And they have the support of the government, which gives them access to the military and the navy, so that they can carry out their controls...”

It is necessary to understand the violent conditions that exist in these areas: There is a context of systematic dispossession of fishing and gathering communities’ territories, and therefore a loss of income and food sustenance for them. People living near the ponds—even ponds that are certified—experience the same conditions of impoverishment as they did a decade ago. For example, in the district of Guayaquil in Guayas province, where the industry’s largest production is located, poverty levels for Unmet Basic Needs are at 47%.

And yet shrimp companies receive credits and subsidies from the national public bank and from international banks—such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private sector arm—to drive their destructive activities. The industry also benefits from special sector insurance, state-subsidized electrification programs and tax exemptions.

On top of this, we must add the constant promotion to open their markets. Since 2014, Ecuador and the European Union have been negotiating a trade agreement that benefits this industry by giving it better access to European markets. And in 2016, Ecuador signed the Multiparty Trade Agreement with the European Union, which, among other things, ratified tariff preferences for the exportation of shrimp produced in ponds.

Job creation is the main argument used to bestow huge benefits on this industry. Industrial shrimp ponds currently cover 250,000 hectares. Comparing this figure with total job creation in the sector, the proportion would work out to be one job per hectare occupied—which is much lower than what a hectare of mangroves represents for families in the estuaries. A worker in the Gulf of Guayas said in 2019: “There are three of us working at this shrimp farm—the pump operator, the manager and the guard. Each of our average salaries is US $400, but it is a 24-hour job. We do not have a contract, and we could be fired at any time.”

Women are generally hired at the packaging companies to clean and remove the heads of the shrimp. The following testimony from 2019 is from fisherwomen and gatherers from the Puerto Bolívar area, El Oro Province: “A woman can make up to twelve dollars in about four hours, if she manages to peel 100-120 pounds of shrimp, since they pay $0.10 per pound. The job is every aguaje; that is, every eight days you can get half a day of work, depending on whether there is a harvest and whether there is enough work, because there are many women who offer their labor.”

Concealment through certification: the Omarsa company

Since 2000, shrimp certifiers have been in a consolidation process. Currently, at least nine industrial shrimp aquaculture certifiers have been identified in Ecuador (2).

>From 2008-2018, one of the largest companies in the sector, Omarsa, took advantage of the government-sponsored regularization. This “regularization” has given it access to certification, among other things. Omarsa has managed to obtain eight certifications.

Located in the province of Guayas and owned by the Banoni family, Omarsa today has 3,735 hectares of ponds, and it controls the chain of production, processing and national and international marketing of its product.

On its website, the company says it has reforested 98 hectares of mangrove forest, which is 3.3% of the total area its ponds occupy—instead of the 30% required by the Decree. With 3,375 hectares, Omarsa should have recovered at least 1,000 hectares of mangroves.

Meanwhile, Omarsa claims that it has created 6,391 jobs throughout the whole chain of production; that is, from farming to export. It seems like a large number, but if this figure is related to the number of hectares of mangroves occupied by the company, it is determined that the generation of jobs is only of 1.71 for each hectare occupied.

In regards to its “environmentally sustainable” production, the company says that it does not use chemicals to cultivate and raise the crustacean. But it does not report on other data, such as:

- Water management: It is unknown whether water is treated or analyzed for quality before it is returned from the ponds back to the estuaries.

- The reforestation of 98 hectares: There is no indication of integrated management with a focus on restoring the mangrove system, which would imply the reproduction of biodiversity, the quality of hydrodynamics, and the decontamination of the substrate, among other things.

- Feeding based on fishmeal: Pelagic fish, which are valuable food for fishing and gathering communities, end up being turned into tons of fishmeal for the shrimp industry.

As for social responsibility, the company points to three projects, which, based on what can be inferred from its website, are financed through external contributions (donations): Water for the community: a tank to extract groundwater from a well in the community of El Zapote, benefiting 100 inhabitants. They also take water to the community of Cerrito de los Moreños, located in the Gulf of Guayas, benefiting 600 inhabitants; Sewing workshop: located in a neighborhood near its processing plant in Guayas province. The goal of this project is to train 25 women; and Housing reconstruction: aims to rebuild the homes of a total of 25 workers, who are considered to be in an especially vulnerable socio-economic situation.

Guaranteeing access to water and housing is a duty that the state should fulfill for the well-being of its inhabitants. With the state not fulfilling this obligation, companies take advantage of this precarious situation, seeking to improve their image and draw attention away from the real impacts caused by their industrial activity.

Twelve community members interviewed in the Gulf of Guayas in late 2019 said they were unaware of the company’s social and environmental responsibility projects. It was impossible to locate a single community member who had participated in mangrove reforestation within the company’s concession area. Two residents of the Cerrito de los Moreños community confirmed that the company “gives them water when they send water to the ponds.” No one interviewed knows how the certification process occurred, much less about the certifying companies and their standards. This reveals the absolute lack of participation of affected communities in this process.

This is the framework in which the Omarsa company has obtained eight certifications; one of these is from the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), started by the NGO, WWF, which has also promoted the so-called Aquaculture Dialogues since 2004.

In light of the contrast between the certification standards and the reality of life surrounding shrimp ponds in Ecuador—characterized by ongoing violations of human rights and nature, hidden behind an apparent “legality”—it becomes necessary to reveal the concealment that these certification companies provide to this predatory industry. Certified companies hide behind the discourse of “sustainability,” without considering that it is impossible for industrial monoculture to contribute to the integral recovery of a biodiverse mangrove system that has been destroyed by more than 70%.

For more information, see the C-CONDEM report, “Cómo la certificación ambiental y social encumbre la violación de derechos humanos y de la naturaleza en Ecuador” (How environmental and social certification hides violations of human rights and nature in Ecuador), August 2020.

Marianeli Torres Benavides,

National Coordinator for the Defense of the Mangrove Ecosystem (C-CONDEM), Ecuador

(1) Certificando la Destrucción, C-Condem, 2017

(2) The certification companies in Ecuador are: ASC - Aquaculture Stewardship Council; MSC – Marine Stewardship Council; BEST Aquaculture Practices; BRC Global Standard; Control Union Certifications - European Union Organic Production Certification; SQF - Safe Quality Food; Naturland; Global Gap; BCK Kosher Certification.