The Palmas del Ixcán company has imposed itself on Guatemala, through what communities call “systematic dispossession”. It has used multiple tactics to grab land, as well as a deceptive RSPO certification process and the use of “independent producers.” Despite criminalization of communities, their resistance grows ever stronger.

Oil palm is not traditionally grown in Guatemala. When palm companies arrived in the Municipality of Ixcán in the state of Quiché, or what is called the northern lowlands, they did not evict people to plant palm. Rather, they did so much more strategically. We call what they are doing systematic dispossession.

Traditionally, indigenous peoples in Guatemala manage land collectively. There are no bosses and no owners. Since the 1960s there have been “development” plans in the country, which have included the Xalalá Dam, oil exploration and exploitation, and oil palm. A highway called the Franja Transversal del Norte was built in order to transport these products. The Municipality of Ixcán, created just in 1985, was one of the municipalities most affected by the internal armed conflict (1960-1996). Because it is a completely forested area, Ixcán was where the guerrilla movements gained a lot of momentum. The intention was to fight against all the injustices of the political system, and that is why many of our grandparents and even parents took up arms. At the height of the conflict, several companies had to withdraw from the area due to pressure from the guerrilla movement. However, after the 1996 peace accords, the strategy of systemically dispossessing people resumed.

Of the 12 peace accords, the Agreement on Socioeconomic Aspects and the Agrarian Situation was key. In this agreement, an alliance of guerrilla groups—there were four groups which ultimately formed one alliance—along with other sectors, such as the Catholic Church and international observer groups, proposed a just distribution of land to do away with the system of servants and bosses. In the Agreement, the State of Guatemala committed to creating mechanisms for people to access land, such as the Land Fund and the Secretariat of Agrarian Affairs. But from 2001-2002 on, the Guatemalan State began to promote private land titling through the Land Fund. That is, each person had to have a document ensuring individual, not collective, ownership. This ignored the way indigenous peoples had managed their lands. This process lasted six or seven years in some communities. The Municipality of Ixcán was one of the first regions to implement private land titling. There are around 30 communities in the region, 12 of which are affected by palm.

Coincidentally, three years later, the government of Álvaro Colom set up a trust so that other companies could obtain money and offer agricultural credits to communities. Many communities fell into the trap. They decided to accept, and when farmers were given their individual deeds, they were told: “You are now the property owner. If you want to sell now, you can. You can take out a loan and you can pawn your lot.” Many chose to get agricultural credits. Between 2008 and 2009, 17 companies offering agricultural loans appeared in the Municipality of Ixcán. They took advantage of the fact that people had many needs following the conflict. Through this mechanism, people could pawn their land deeds in order to obtain loans. This municipality happens to be below sea level, and almost every year there are floods, and crops are lost. Logically, people could not pay back their loans. In many cases, two or three years went by in which they were not charged. When they began to ask about their credits, they were told: “Don’t feel bad, the palm company has already paid, and they have the deed now, they are the owners.” In other cases, people offered their land to the “coyotes,” the frontmen for the company who showed up offering to buy lands to grow corn supposedly. This is how the Palmas del Ixcán company got a lot of land.

Another case that illustrates the company’s tactics is that of two people who decided to sell their plots to the company. Since they could not read or write and their language was Q'eqchí, the company asked for two witnesses to endorse the document of sale. They then took four people to Zone 10 of Guatemala City, the most exclusive area, and made four documents of sale. That meant that the people who were supposedly signing as witnesses were actually signing a document that handed over their lands to the company. One of the Q'eqchí-Spanish interpreters noticed this and filed a complaint against the company and the public notary who promoted this situation.

Another tactic they use is to buy out the person who is at the edge of, for example, the cultivation area, and then the next person; and if that person doesn’t want to sell, they buy from the person further ahead. This way, whoever is in the middle has to go through the plantations, and this prevents them from working freely; they therefore have to sell. Or, companies look to the local authorities and get them to become “coyotes” or a front for the companies in order to obtain plots. So there are several strategies. That is why we call it systematic dispossession.

Impacts, violence and precariousness

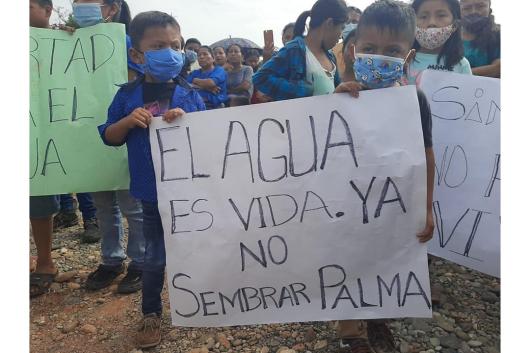

Water pollution and scarcity have generated more awareness about the multiple impacts of palm monoculture. This issue has made communities aware of other impacts and has forged the resistance that currently exists in communities. This region used to get flooded quite a bit, but since 2018 it has been one of the regions most affected by droughts, leaving people without crops. People now understand that the greater the destruction of diversity, the greater impact the droughts will have on the territories.

Now in the lowlands, where there is still too much water, the company is making some ditches to drain the water. These ditches are carrying chemical waste pollutants into rivers.

There is no palm oil extraction plant in Ixcán Municipality. Fruit is just harvested there and transported to Chisec Municipality, on the other side of the river, where it is ground to extract the oil. All of the waste from this process goes directly—without any kind of treatment—to the Chixoy River (or Black River), one of the largest rivers in the country. Residue from the fruit, called raquis, causes fly infestations that get into homes. Flies are in the food, on clothes, they are everywhere; and as a result they transmit diseases, mainly stomach diseases in children. There is so much waste that the fly infestation has reached Ixcán Municipality.

In the case of the community of Sonora, after a 2018 investigation by the Ministry of Health, the prosecution authorities of Guatemala investigated the chemicals present in the Sonora River. The results were obtained at the beginning of 2021, and the presence of chemical products was verified. All of them were tied to palm and the Palmas del Ixcán company. The case went to court. After that, the company filed a complaint against community authorities for aggravated usurpation and illegal detentions. The company wanted to continue working on the community’s lands, and the community ran them off. The company argues that the community is trying to take away its lands, yet it has not presented documentation that proves it owns those lands.

So, there is no more water and no more organic matter on the land. The water is no longer going through its natural process of rising in vapor form and returning in liquid form. All the water is filtered, and the artesian wells that the people use for their consumption dry up. Women now walk up to two or three hours to fetch clean water in other communities; some even cross the border into Mexico. These are very severe situations.

Meanwhile, community authorities are criminalized and coopted. Companies take over community roads. They co-opt leaders however they can in order to engender conflicts in the community. And the companies are good at marketing and at hiding everything that the community says. Palm oil is environmentally friendly, they always say, despite communities’ testimonies to the contrary.

One example of marketing tactics is labor exploitation. The Palmas del Ixcán company claims that it is paying its workers very well, because the minimum wage for agricultural work, acocording to Guatemalan law, is around 79-86 quetzals, and the company is paying 98 quetzals a day (US $13 approximately). But the company never mentions the amount of work. For the job of plateo, that is cleaning around the palm plant, people are assigned 250 plants per day. This means that they are making around 48 cents per plant. That is the same amount the Germans paid their grandparents when the latter were dispossessed to grow coffee a hundred years ago. If they do not complete the task, they are not paid; the next day they have to complete the previous job as well as the current day’s job. Furthermore, they almost never have contracts and therefore have almost no labor rights (1).

The elders here are very wise. They say: “You cannot have two hearts. One heart with the company and another with the community is not possible. You are either with the community or you are with the company. It’s simple. You cannot have two hearts.”

RSPO Certification

The Palmas del Ixcán company says that it is fully certified. We know that the company is RSPO-certified for the product, but we do not know when they were granted this certification. The communities have no idea of what happens at that level, nor do they have information about what certification entails.

We filed a complaint to the RSPO; we also participated in a consultation mechanism with this entity, but this was about the new plantations that the company planned to implement, not about existing production or plantations.

When we accompanied the communities in consultations with the company about new plantations, some unpleasant things happened. The consultation document mentioned a first visit already made to the communities in May 2019, and it claimed that six Ixcán communities in the plantation area had already accepted the new plantations. Palmas del Ixcán had hired the company, IBD Certificaciones, to supposedly conduct consultations with the communities. Yet when we spoke with the communities, they told us they did not know anything about this. In other words, it was not true that they had visited the communities.

At the time, we sent briefs to the RSPO explaining this. Then, a person from IBD contacted us to have a meeting. He wanted to have a meeting with each community separately. As for us, we consulted with the communities, and it was decided that the meeting would have to be with all of the communities together, not separately, because we didn’t know what kind of manipulation strategies they might use. IBD accepted this and we told them to come so that we could explain the whole situation. At the meeting the person said he did not know what was happening with the palm company. But when he told us his name, we realized he was the same person who had signed the previous report—the report that the communities considered to be false. Nonetheless, a brief containing all the minutes from the meetings was done, stating that that report was false. This brief was given to the IBD representative, sent to the RSPO, and disseminated in alternative media channels.

Nonetheless, the RSPO’s recommendation to the company was to approach communities to try to convince them. There was no other way to interpret its response. In December 2019, Palmas del Ixcán wrote the Social Intercultural Movement of the People of Ixcán asking us to meet with them. We did not, of course. The company should have communicated with and met with the communities. After that, there were other proposals for dialogue, which we passed on to the communities because they had not been invited. They expressed they were not in agreement.

That was the perfect excuse for the RSPO to grant certification. When we later criticized the RSPO for certifying Palmas del Ixcán, their response was that the company had approached the communities and the communities did not want to dialogue.

In 2019 we issued the declaration, “The RSPO is a sham,” because we believe that the RSPO’s purpose is to plant palm at any cost, and that the motive behind approaching communities is to continue to plant it (2).

In response, the RSPO wrote to us again via its representative, Francisco Naranjo (Latin American Director for the RSPO), to tell us that the certification was already done. Francisco Naranjo has not been to the communities. As we say in Guatemala, “he couldn’t care less” what the communities are experiencing, so the communities are not going to obey the certification either.

The communities have decided that they will no longer allow palm to be planted on their lands. Six communities were in the process of certification for new plantations. After all of this, five of them are now informed about the impacts, but not all of them. One community has authorized companies to plant palm.

Small farmers program: “independent palm producers”

We were very surprised by the 2019 agreement between Palmas del Ixcán, US company Cargill, and the Dutch NGO Solidaridad. We were struck by the fact that in a very difficult moment for us, just as we were examining what would be presented to the RSPO in response, the corporate media came out with this agreement as great news.

The “independent palm producers” process had already been in the works. There is nothing independent about it. Palmas del Ixcán is the one that sets the prices and all the conditions, and people cannot sell to any company other than them. Supposedly, the support families have received from the company is technical training on palm management and harvesting. But we must not forget that the same drought that was caused by palm, also affected palm. In the last two years, palm production has been much lower than in previous years. Therefore, there has been a lot of pressure on “independent palm producers;” they have to produce the same amount of palm as stated in the contract, regardless of what happens.

There are more than 100 “independent palm producers” in Ixcán, and each one has been given a pair of goats to help eat the vegetation underneath the palm trees. In practice, these so-called “independent palm producers” are the company’s support base. When communities in resistance publicly denounce the RSPO or other entities, it is the “independent palm producers” who tell a different story than the communities.

While there are a lot of reservations among the communities, it is the women who really do not accept palm under this scheme. In many families, the men agree to be “independent palm producers” and it is the women who are opposed, who say: “No, not in this family, our land is not for that.” There is already a lot of awareness and organization among women. They are the ones who have been on the frontlines of the communities that have started to resist palm—palm grown both by the company and by “independent palm producers.” They live with the problems of water scarcity and contamination up close.

Resistance

The institutionality of the Guatemalan State is being highly criticized by the population. Regardless of the will one could have, and even if there were investigations carried out and complaints filed against palm companies, what State institution would dare follow up on a complaint against the palm companies? Within the CACIF (Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial and Financial Associations), which is made up of business leaders in Guatemala, billionaire palm companies make up the Chamber of Agriculture, which has much more influence than any other chamber. It is quite complex and riddled with corruption. So communities despair, and in many cases do not even file complaints. The resistance is therefore focused on the territories.

In La Sonora, where the water pollution complaint was made, residents decided to reject the palm company’s development proposal. They did so in a meeting that took place in June 2019, and they cut all ties with anything related to the company. They stressed that everything they have built in the community has been with their own resources and is a result of their work. They recorded this in a communal record, and it was agreed that the Palmas del Ixcán company would be asked to withdraw from their territories.

Two years ago, the community of Prado decided that it would no longer allow palm to be grown on its lands. In July 2021, when the company arrived, the community stopped the trucks that were transporting the plants, and forced them to turn around and not plant palm there. The company filed a writ of amparo before the Court of Appeals so that it would invalidate the community’s decision.

The communities of Ixcán Municipality, as in all of Guatemala, have the right to decide what is and what is not grown on their lands.

Herbert Sandoval,

Social Intercultural Movement of the People of Ixcán, Guatemala (Movimiento Social Intercultural del Pueblo de Ixcán, Guatemala)

(1) Communities denounce labor exploitation at palm company, La masa, March 2020

(2) Movement of communities in defense of Q'ana Ch'och' water and the Social Intercultural Movement of the People of Ixcán, October 2020