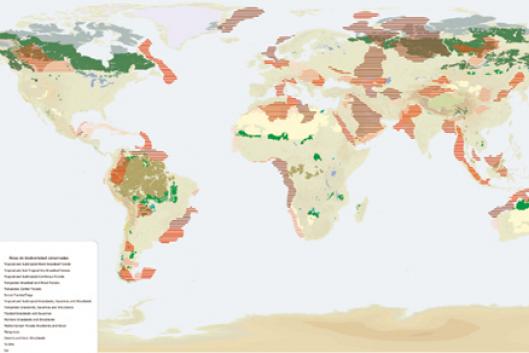

Oil has been historically extracted disregarding the costs that the process entails to the local people and the environment. Thus oil extraction has become a direct cause of the deforestation of large areas of tropical forests where some of the world's most promising oil and gas deposits lie, degrading the forest as a whole through its impacts on water, air, wildlife and plants.

Furthermore oil drilling constitutes an underlying cause of deforestation and forest degradation because it opens up the forest enabling logging and forest conversion to agriculture and cattle rising.

Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Nigeria have substantial oil operations in rainforest areas ravaged by the deforestation caused not only directly by the process of oil drilling but also by the construction of roads through the forest that allow remote lands to be open to developers in search of oil. Toxic by-products are usually dumped into local rivers and persistent oil spillages result from broken pipelines and leakage.

Oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon

In Ecuador, current exploration campaigns are concentrated in the north of the Amazon region, especially at the foothills of the ‘Cordillera Oriental’. This area is the ancestral territory of the Cofan, Siona, Secoya and Waorani indigenous people. It is also the territory of the Napo-Kichwas and several Shuar families that settled there during the rubber boom. There are attempts to bring oil exploitation also to the South of the Amazon in the next round of oil concessions in 2013.

Before oil activities arrived to this part of the Amazon the main characteristics of the area were:

1. Hunting, fishing and gathering.

2. Itinerant agriculture that allowed the indigenous peoples to conserve and create productive soils in zones where the previous conditions of clay soils did not allow agricultural practices; and generate and preserve-biodiversity in these tropical forests.

3. Cultural, religious and recreational activities through land use regulation and respect of the territory.

The first economic activities directed to external markets were rubber and timber. Then along with oil expansion, new protected areas were created such as the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, the Yasuní National Park, the Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve, the Limoncocha Biological Reserve.

The impacts of oil extraction in the Ecuadorean Amazon have been well documented, especially due to the case against Chevron-Texaco that operated for 26 years in the North-Eastern part of the country. In this period, Texaco drilled 339 wells across 430 thousand hectares. It extracted more than 1500 million barrels, discharged billions of barrels of toxic formation waters and other toxic wastes, and flared billions of cubic feet of gas. Although it is impossible to put a price on nature, because life cannot be measured in money terms, the damages of the company´s actions have been calculated in the tens of billions, due to oil spills, marshland contamination, gas burning, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, wild and domestic animals killed, appropriation of natural materials, river salinisation, diseases (31/1000 cases of cancer when the national average is 12.3/1000), underpaid jobs, and the list goes on …

On February 14th, 2011 the court decision in the ‘trial of the century’ established that Chevron-Texaco was liable for a USD 9.5 billion fine. The judge ruled that if Chevron Texaco didn’t apologise in public in 15 days, the amount would be doubled as punitive damages. The deadline expired and the company now owes USD 19 billion. This must be one of the largest settlements awarded in any trial.

The company has refused to pay, despite a failed appeal whereby on January 3rd, 2012 a three members tribunal ratified the original decision.

Ecuador: an oil country

The proposals for moratoria and oil-free territories have emerged from very diverse front lines, uniting movements against war, urban expansion, consumerism, the destruction of oceans, the spread of cancer and its causes, and indigenous peoples’ movements.

It has become clear over the last century that fossil fuels, the energy sources of capitalism, destroy life − from the territories where they are extracted to the oceans and the atmosphere that absorb the waste − through transformation and consumption. The oceans are acidifying and the atmosphere contains more and more greenhouse gases. Fossil fuels, under the guise of ‘energy security’ promote violence across the world, in the process building and sustaining inequalities regarding who pays the costs for the extraction and also in access to energy.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Ecuador began extracting oil, first on the coast and then in the Amazon region. It started to export oil in the 1970s. In the 1980s, Ecuador’s timid efforts to establish a sovereign economy, including the development of secondary industries, were sidelined as the debt crisis across Latin America led to the imposition of neo-liberal adjustments that forced the country to depend on a primary-export economy.

Oil thus moved to the centre of the economic activities of the country; and Ecuador started to suffer from the so-called ‘Dutch disease’, the symptoms of which include the decline of other productive sectors.

The first phase of oil extraction was marked by a total lack of control over concessions. This was followed by a stage marked by nationalism. In this period, oil was nationalised and the state oil company CEPE was created. In its first years CEPE formed a consortium with Texaco. Subsequent governments established neo-liberal policies in contracts with private companies, weakening the state oil company.

Ecuador’s first oil exploitation area was the Santa Elena Peninsula. It is unknown how much oil was extracted there. However, Ecuador was internationally recognised as an oil country when petroleum was discovered and extracted in the Amazon region. From a political economy point of view, Ecuadorian leaders would be wise to take into account the interaction between different factors such as the characteristics of the oil industry, and the territories and the power relationships built around the oil metabolic cycle.

According to Acosta (2009), oil activities involve diverse social and environmental effects:

• Significant income generation. • Expensive investments. • Difficulty in accessing reserves which means building infrastructure (roads, electric plants, airports, pipelines, etc). This leads to the creation of debt as national investments need huge amounts of money obtained mainly through the financial system; when a country pre-sells its oil barrels a percentage of the oil export incomes goes to pay for the previous debts. • Technological dependence: Ecuador lacks its own technology and thus depends on foreign expertise (for example, oil exploration was executed for the most part by Halliburton in the past and nowadays by the Chinese Sinopec). • Increased dependency and growing national consumption of petroleum and related products such as plastic, liquid petroleum gas (LPG) and gasoline • Oil economies are marked by a lack of control over international price variations on the global market. • There are severe social and environmental impacts that provoke diverse local resistance processes. • National sovereignty is systematically lost, especially in terms of oil policies, waiving rights in contracts, price-fixing and the institutional framework around oil activities.

Extractivism of the 21st century, from neo-liberalism to state capitalism

According to Ross (2001), Ecuador shares many characteristics with other countries that depend on non-renewable resources:

1. Weak State institutions that are not capable of properly enforcing the laws nor controlling the actions of government. 2. Absence of rules and transparency that encourage high levels of discretion in the management of public resources and the commons. 3. Conflicts in the distribution of revenues between powerful groups that strengthen rent-seeking and patrimonialism. This leads to a blending of the public and private sectors and in the long term decreases investments and economic growth rates. 4. Short term policies 5. Low values of social indicators, such as literacy, high infant mortality, etc…

In the neo-liberal phase (from 1985-2007), the state offered extremely favourable terms on oil revenues so as to attract foreign investments. From 1985 onwards, Ecuador called for new oil bidding rounds that expanded the geographic limits of the oil frontier to the East, towards the Yasuní National Park. These oil bidding rounds were part of a strategy of trade opening that stemmed from indebtedness and therefore the need to pay debts back, and the retreat from nationalistic policies.

The government of Rafael Correa, which came to power in 2007, stopped external debt payments and is more nationalistic than past governments. However, it has not distanced itself from the extractivist logic but on the contrary has maintained it, due to the opportunity offered by high oil prices to increase government revenues and invest in public works and also in welfare payments.

Ecuador has insufficient refining capacity. Therefore the country exports oil but then imports oil products in increasing amounts because of economic growth. It aims in the long run to increase refining capacity but for the time being, the aim is to export more and more oil every year. As existing oil fields become exhausted, this implies expanding the oil frontier in the Amazon region.

These new oil frontiers include protected areas (such the Yasuní National Park) and indigenous territories in the central-south region of the Amazon. These regions contain extra heavy crude as in the remaining important reserves inside indigenous territories, for example in Pungarayacu and in other areas of the Kichwa peoples in the Napo region. There is also a desperate search for oil along the Ecuadorian coast.

Oil concessions in the Amazon in 2007 covered 5 million hectares; 4.3 million of them conceded to foreign companies. In 2011 these numbers doubled with the incorporation of 20 more oil blocks. In light of the re-election of Rafael Correa in 2013, the oil frontier can expect to be expanded to the south-east at the cost of many local complaints. Since 2007, Correa’s has been the most extractivist government in the history of the country, in terms of oil and now also mining.

Today the belief still prevails, also inside the government, that oil and mineral resources are essential for the development of the country and for the satisfaction and provision of basic rights such as health and education. There has been no widespread and democratic reflection on the limits of the extractivist economy.

Threats to Yasuní

Some of the expected impacts should oil exploitation take place in Yasuní ITT are:

Waste Products

The oil industry admits that for every vertical well that is drilled 500 m3 of solid waste and between 2,500 to 3,000 m3 of liquid waste produced.

Production Water

Produced water is briny fluid trapped in the rock of oil reservoirs. It is by far the largest toxic byproduct of the oil industry. If the ITT oil reserves contain 846 million barrels, then their exploitation would mean about 400 million m3 of oil production waters. The re-injection of all this water is impossible. These salty and toxic waters would end up inevitably in the Yasuní park itself.

Deforestation

Deforestation is one of the habitual effects of oil activities in the Amazon and some other regions in the world. It occurs while building roads, campsites, heliports, along the pipeline routes and other infrastructure needed for these activities. It has been estimated that every new road built impacts 100 metres of forest on either side, creating a border effect. Roads break the migration routes of the natural fauna, affect the distribution of flora and constitute a permanent threat to the peoples living in the area. However, the most significant cause of deforestation is the indirect deforestation associated with the building of roads for infrastructure maintenance and that brought on by the colonisation by settlers generated by the project itself.

In block 31, the Apaika and Nenke platforms are inside the Yasuní National Park. The project plans to build diverse oil facilities such as a Central Processing Facility (CPF), 30 km of pipelines, campsites, heliports, both permanent and temporal, transmission lines, roads, 14 wells and 2 platforms.

Climate effects

Oil activities produce ex situ and in situ emissions. The oil industry requires large quantities of fossil fuels. It is estimated that for every 10 barrels extracted, one is burned in the same place. The situation is worse when the oil is heavier (as in Yasuní) and when the well is at the end of its useful life. The heavy oil must be pumped and this requires energy. Finally, ex situ, burning ITT crude would generate 407 million tonnes of CO2.

These figures do not take into account the emissions from local direct and indirect deforestation, and the gas flaring. ITT oil exploitation would increase road building, colonisation, illegal activities such as logging and biopiracy, and it could promote the expansion of illicit crops.

Psychosocial impacts

In addition to pollution and environmental devastation, oil activities disrupt community life. There is evidence in other areas such as the Waorani’s indigenous territory where these activities have generated alcoholism, prostitution and introduced different diseases (ranging from lethal diseases to mild ones such as obesity or malnutrition due to changes in eating habits).

ITT and block 31 are located inside Waorani territory, as well as the hunting grounds of other indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. These are traditional hunter-gatherer societies that move throughout a large area inside the park’s borders, sometimes reaching the oil blocks. Oil activities bring disease, impoverishment, conflicts and other social ills. The territorial occupation by oil companies is accompanied by the installation of military camps, bars, brothels, roads, small businesses from outsiders, etc. All of them provoke social and cultural conflicts for the native peoples.

The ITT Yasuní Initiative: an initiative for life

The Yasuní proposal for leaving oil underground evolved with the key strategic aim of confronting the oil development model head-on, simultaneously attacking its capacity to impose itself at the local level, and expanding critique to the national and international level.

From its beginnings it included the arguments and the struggles of the communities against oil policies and projects, allowing for the recognition of the peoples that have resisted, not only protecting their own territories but defending the planet as a whole.

At the national level, the initiative included a profound questioning of the extractivist model. At the international level it aimed to question the environmental injustices of the carbon markets and the neo-liberal policies regarding climate change that impose false ‘green solutions’. The most direct way to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide is to leave fossil fuels in the ground.

Excerpted and adapted from: “The Yasuní – ITT initiative from a Political Economy and Political Ecology perspective”, by Esperanza Martínez, in” Towards a Post-Oil Civilization”, EJOLT Report No.: 06. The full report can be read at http://www.ejolt.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/130520_EJOLT6_Low2.pdf