Water is not just water. The importance of water is often reduced to its commercial value and its use as a natural resource—that is, its economic use. This reductionist approach commodifies the different vital uses, relationships and possibilities of water. Furthermore, this approach sees nature as if it were an inexhaustible storehouse; an eternal supply of goods; a machine; an isolated thing that does not have life.

Indigenous Peoples offer us different visions and ways to establish healthier and more interconnected and meaningful relationships with nature and water.

A wise woman of the Awajún people, Irma Tuesta, tells us: “Our territory is connected to everything, because everything has life for us. Everything has a mother: the water, the air, the forest, the earth, the stones, the hills, the birds, the animals, the plants” (1). For her, nature is a vital unit, a whole of life formed by various threads of lives. In this case, ‘life’ must be understood not only as a ‘force’ or ‘energy’ in living beings, but also as an ongoing activity, as a journey, as a story, as an experience of living life.

Irma goes on: “The territory is our life, as is everything that has to do with the territory—our knowledge, our wisdom. We transmit this to our children through stories, poetry and songs, and by protecting our territory.”

The last words further illuminate this concept. The territory—that is, the rivers and the forest as a whole—is life itself for indigenous peoples. It is the area where their knowledge, their memory and their existence are produced and contained. Their life is their territory. Apu (indigenous leader) Alfonso López of the Kukama people, and president of the federation, ACODECOSPAT (which represents 63 Kukama communities from the Marañón, Ucayali and Amazonas river basins in Peru) says: “The territory is within us; we are the territory. You stop being indigenous when you disconnect from your territory, when you no longer have a relationship with your natural space. You stop feeling indigenous when you stop feeling the power of your nature, the power of the spirits of the plants that feed you, […] But how can we have a vision if everything is sick? How can we see the future clearly if they are making us sick, if they are destroying us?... and just to seek economic resources” (2).

The norm does not cover the fullness, but it has substance

Different multilateral organizations exist to ensure access to water as a human right, and to protect indigenous people’s territories. The UN has recognized access to water as a human right since 2010. Meanwhile Convention No. 169 of the ILO—which has constitutional rank in Peru—specifies that States must adopt special measures or establish safeguards to protect and preserve territories that indigenous people inhabit, with the aim of ensuring their cultures, knowledge and productive capacity, among other things. There are also many other references and international jurisprudence on this subject.

Since 2017, the right to access water has been constitutionally recognized in Peru through Law No. 50588. This law only prioritizes human consumption of water over other uses; however, it associates access to water as starting point to access other rights, such as “dignity, free development of the person, the environment, work, and identity, among other rights” (3).

But the Peruvian State breaks its own norm, and does very little to reverse the backsliding of this right. According to the Ministry of Culture, 54% of the Amazonian indigenous population does not have access to water via public infrastructure. While this figure seems conservative to us, the ministry’s report indicates that this is a big difference compared to the Spanish-speaking population, of which only 11% does not have access to this service (4).

Meanwhile, the Ombudsman Office in Peru published a report in 2018 on the health situation in indigenous Quechua, Achuar, Kichwa and Kukama communities along the Pastaza, Corrientes, Tigre and Marañón rivers, respectively (5). The document says: “Regarding access to safe water for human consumption, the situation is more extreme. In the districts of Andoas, Pastaza, Urarinas, Trompeteros and Pariniri, between 97% and 99% of homes surveyed consume untreated water. While in the districts of Tigre and Nauta, that figure reaches at least 66% and 82%.” In its report, the Ombudsman recognizes that this serious situation exposes the population to conditions that increase their risk of developing health problems.

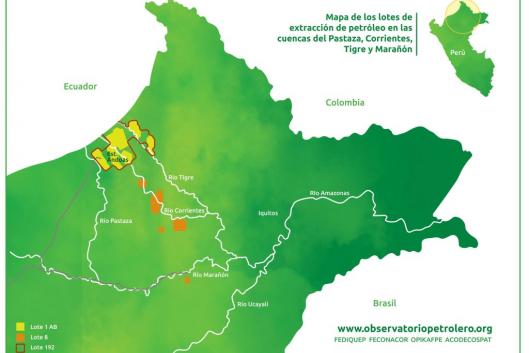

The Ombudsman Office’s attention to the aforementioned districts is not arbitrary. These districts are home to rivers and indigenous communities that are affected by oil activity dating back to the early 1970s, in the oil blocks called 192 (formerly 1AB) and 8. They are also affected by the Northern Peruvian Pipeline, which crosses the northern Amazon and Andes mountains, until it reaches a port on the northern coast where the oil is commercialized.

Almost one hundred communities in the affected areas in the Amazon and their indigenous federations—FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR, OPIKAFPE y ACODECOSPAT—have been leading a unified and coordinated fight for eleven years (6). This campaign, coordinated through the PUINAMUDT platform (Amazonian Indigenous Peoples United in Defense of their Territories), has forged a political and technical agenda that has forced the State to take special measures to address the crisis of oil contamination and rights violations in the area.

Despite the fact that some steps have been taken to deal with the problem, the authorities’ actions have been insufficient, characterized by uneven implementation and, on many occasions, recurring conflicts. Meanwhile, neither oil activity nor its negative impacts have ceased. These damages accumulate and spread impassively.

Oil Block 192 (in operation since the 1970s) was concessioned to the company, Pluspetrol, from 2000 to 2015, and later to Frontera Energy del Perú S.A., whose contract expired in February 2021. The Block is currently waiting to restart operations. Block 8 (also in operation since the 1970s) has been operated by Pluspetrol since 1996, and the concession runs until 2024. Pluspetrol’s main office is officially in the Netherlands. This has allowed the company to avoid taxes on the profits it makes from oil extraction in Peru and elsewhere. Frontera Energy Corporation is a publicly-traded Canadian company with operations in several South American countries.

A vicious cycle: A chain of violations, abuse and damage

A few weeks ago, on June 7, 2022, an oil spill was reported in the indigenous Urarina community of La Petrolera. This community is also located in the Loreto region in the northern Peruvian Amazon, along the banks of the Patoyacu river. The Patoyacu is a tributary of the Chambira river, which in turn is a tributary of the Marañón river. To get there, one must travel by river for at least two days in a high-capacity boat; by canoe (traditional boat), the journey can take three to four days.

Community authorities who reported the discovery could not estimate the amount of oil spilled, but they demanded immediate clean-up actions from Pluspetrol—which operates Block 8, an important oil area in Peru.

Two weeks later, on Sunday June 18, Pluspetrol’s lack of timely intervention caused the oil to reach the waters of the Patoyacu river—which is the source of water, fishing and recreation for the community. “We have been telling them to remove the crude oil for several days, and they haven’t done it. We are the ones who notified the authorities of the spill; it is our territory that is being affected,” the apu of the community, Robles Pisco, told the media (7). Photos shared by the community and circulated in networks also showed fish affected by the spill.

By early July there was still no adequate attention placed on the spill. The community of Urarina continued with its denunciations and claims (8). To date, the community continues to demand that the State declare the area an emergency zone, due to the urgent attention that is required. “We all have headaches and are vomiting. Workers from the company are also sick—they have said so themselves,” said Robles Pisco recently. But the authorities and the company are glaringly silent and absent. The State has only sent delegations to monitor the area.

The tragedy that occurred in the La Petrolera community is not an isolated case. This is not the first time there has been an oil spill in indigenous communities’ territories. According to information compiled by the PUINAMUDT platform and the Amazonian Center for Anthropology and Practical Application (CAAAP, by its Spanish acronym), environmental authorities have registered up to 181 oil spills in Block 8 that occurred between 1998 and 2020. Authorities also count more than 670 impacted sites that need environmental remediation. Despite the fact that Pluspetrol halted its operations in 2020, oil spills that damage the territory and the life of communities continue and accumulate (9).

There is a similar case in the forested areas of Block 192, also located in the Loreto region. According to environmental authorities, there are more than 1,119 impacted sites in this Block (10). Between March 2021 and April 2022 alone, 35 oil spills have been reported. The Kichwa community of 12 de Octubre offers a sad example of what is occurring in the area: two oil spills have been reported in their community in 2022 alone. The indigenous communities affected by this Block have denounced this problem before the judicial authority (11).

Thanks to the denunciations in the last ten years by indigenous organizations such as FEDIQUEP, FECONACOR, OPIKAFPE and ACODECOSPAT, the serious environmental and social crisis that indigenous territories in the Peruvian Amazon are experiencing due to oil spills has been made evident. In most cases, these spills affect various water sources that are the source of life for the forests and their indigenous populations.

Zúñiga and León have systematized information about oil spills in the Peruvian Amazon, showing that environmental authorities have recorded up to 474 spills from oil infrastructure between 2000 and 2019 (12). They have also shown that the total amount of oil-produced waters dumped into rivers, soils and wetlands in the northern Peruvian Amazon reached 7.09 billion barrels between 1974 and 2009. These produced waters contained thousands of tons of different highly toxic chemical compounds (13). It is worth noting that the Peruvian State has had official information since at least the early 1980s, when lead was first reported to be found in sediments, water and animals consumed by indigenous Achuar communities in the Corrientes river basin (14).

Navigating the long journey towards justice and reparations

The critical situation in these territories has a long history and is not new to Peruvian authorities. Yet the current government is not taking decisive actions; it is not ensuring effective actions or policies for reparation, nor is it providing necessary guarantees of the rights of indigenous peoples. “With all of this evidence, we say ‘Enough!’ Enough already. Our own governments are killing us. They are not respecting our rights,” said apu Aurelio Chino Dahua recently—president of FEDIQUEP—at an event in Colombia with the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights (15).

Only after constant social mobilizations, collective denunciations, judicial processes and countless meetings, did the Peruvian state deign to take some actions to address the problem. Faced with the ineffectiveness of different administrations, the communities and their organizations are the ones who proposed the agenda. In 2015, the organizations that formed the PUINAMUDT platform signed agreements proposing concrete actions, budgets and deadlines to address the issues of environment, health, and access to potable water, among other things. The State assumed this agenda by signing a memorandum the same year.

As part of this agenda, studies were carried out that found high levels of contamination in water and soils. In 2016, the Ministry of Health carried out the first toxicological and epidemiological study in the area, which was published in 2019 (16). The study showed that 57% of adults and 49% of children included in the study had levels of lead exceeding the international standard. Additionally, almost one third of the people included in the study had levels of arsenic (28%) and mercury (26%) above the limit allowed in Peru.

A subsequent study in the area, entitled Analysis of the Health Situation (ASIS, by its Spanish acronym) indicates that “access to public drinking water in communities in the four basins and the Chambira river reveals a critical condition […] 56% of people reported that they consume river water despite their perception that it is contaminated.”

So far the State has failed to meet the established agreements—which include those related to water—thereby also failing to meet the obligations it has assumed in international treaties and under the political constitution of Peru.

A forthcoming report by the PUINAMUDT platform explains that when the State has implemented actions related to this commitment (installation of water or sanitation systems in communities, for example), it has done so “without taking into account indigenous autonomy and institutionality, and ignoring its own guidelines and implementation methods. These indicate the State should take into account the cultural differences and experiences of indigenous peoples, as well as the particular characteristics of the territories” (17). In some cases, there have been serious cases of corruption in public organizations tasked with project execution, as well as unjustified criminalization of communal authorities.

To date, none of the commitments signed in 2015 have been fully met.

Despite the critical context, indigenous communities and organizations maintain their commitment to defend life, territory and their rights. The fight they have undertaken is against the tide. On July 15, 2022, in a meeting with the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, the president of FEDIQUEP denounced the State’s negligence in regards to a Health Plan that would attend to more than 500 indigenous communities. President Pedro Castillo’s administration has avoided approving this plan for more than seven months.

Such is the poor level of commitment to the rights of Indigenous Peoples by the current, self-proclaimed leftist government. It is clear that its position is the same as previous, openly neoliberal governments. In this context, organizations and Indigenous Peoples are keeping their spears raised. Such is the constancy and direction of the rivers, which guide the way to defend life in the Peruvian Amazon.

Renato Pita Zilbert

Communicator, PUINAMUDT Platform

July 2022

(1) Various authors. (2020) ¿How do we understand our rights? Webinar: Series of talks on the rights of indigenous peoples. Visión Amazonía, Perú Equidad, Caaap, Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, IWGIA, NICFI. Lima, Perú

(2) Alfonso López, in the Public Forum “30 years after Convention 169, What is the situation of indigenous peoples in Peru?” (2019). Ruiz de Montoya University, Lima. Transcription by David Díaz Ávalos

(3) Cacñahuaray, Ruth. El acceso al agua potable en las comunidades indígenas del Perú en el marco de estado de emergencia nacional. Revista Eurolatinoamericana de Derecho Administrativo, vol. 7, núm. 2, pp. 261-277, 2020. Universidad Nacional del Litoral

(4) Peru, Ministry of Culture, Indicators – Water service, 2018.

(5) Defensoría del Pueblo. 2018. «Salud de los pueblos indígenas amazónicos y explotación petrolera en los lotes 192 y 8: ¿Se cumplen los acuerdos en el Perú?»

(6) The platform is called Amazonian Indigenous Peoples United in Defense of their Territories (PUINAMUDT): www.observatoriopetrolero.org

The participating indigenous federations are: Indigenous Quechua Federation of the Pastaza River (FEDIQUEP); The Federation of Native Communities of the Corrientes river basin (FECONACOR); The Organization of Kichwa Amazonian Indigenous of the Peru-Ecuador Border (OPIKAFPE); and the Cocama Association for the Development and Conservation of San Pablo de Tipishca (ACODECOSPAT)

(7) PUINAMUDT, Triste día del padre: Pluspetrol no atiende a tiempo derrame de petróleo y empieza a contaminar quebrada Patoyacu, junio 2022.

(8) PUINAMUDT, Alerta de emergencia ambiental y sanitaria en comunidades urarinas por derrame de petróleo en el Lote 8, julio 2022.

(9) Since the end of 2020, Pluspetrol as halted its activity in Peru. Indigenous organizations have denounced that the company intends to abandon Block 8 (its contract expires in 2024), in breach of its environmental obligations, just as it did in Block 1AB. The company and the Peruvian State are currently in an arbitration process due to corporate liquidation that Pluspetrol is seeking.

(10) PUINAMUDT, Ministerio de Energía y Minas desaprueba por segunda vez propuesta de Pluspetrol para remediación del Lote 1AB, febrero 2019.

(11) PUINAMUDT, Federaciones indígenas denuncian penalmente a Perupetro por derrames sin atención en el Lote 192, abril 2022.

(12) La sombra del Petróleo (2020).

(13) Yusta-García, Raúl. 2019. Contamination of water and soil due to oil extraction in the northern Peruvian Amazon. Doctoral thesis. ICTA-UAB (Barcelona, Spain). The author also points out that the volume identified in the Peruvian Amazon is 15.7 times higher than the PW (produced waters) discharged in Ecuador from 1971- 1992 by the Chevron-Texaco oil company (page 81)

(14) Maco, J., R. Pezo, J. Cánepa. 1985. Effects of Environmental Contamination from Oil Activity.

(15) Apu Aurelio Chino Dahua in the United Nations Regional Forum for Latin America and the Caribbean on Business and Human Rights (July 2022 in Bogotá, Colombia) (julio 2022 en Bogotá, Colombia)

(16) PUINAMUDT, Ministra de Salud entrega informe final de estudio sobre metales pesados a dirigentes indígenas de Loreto y se compromete a implementar un plan de atención, julio 2019,

(17) The report is in the final stages of editing, and was prepared by anthropologist Diego Navarro at the request of the federations of the PUINAMUDT platform.