Behind many appealing products in the supermarkets of major urban centers in the world, there are countless silenced stories. Behind the good-looking "green label" certification, the content of products and the large amount of paper wrap, there's a story to tell about consumption and water pollution. It would be more appropriate to call this consumption: water theft. Considering that to manufacture these products and to use its raw materials many communities in the South are running out of drinking water. It is important to give visibility to this reality, but it becomes even more crucial when companies such as the transnational company Procter and Gamble hide this robbery behind an action of "social responsibility" that focuses on water.

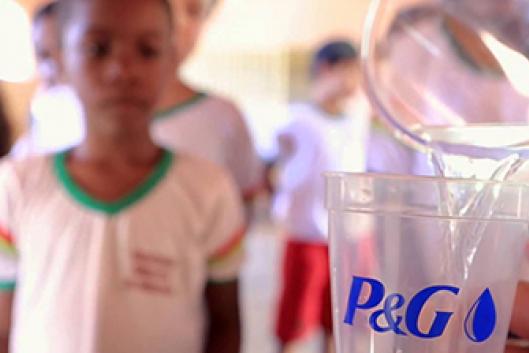

Some years ago, Procter and Gamble (P&G), one of the largest companies in the world which manufactures products for supermarkets in the United States and other countries, launched its “saving lives” campaign (1). PUR packets or bags with a “purifying” substance that would be able to transform dirty water into clean water are distributed in dozens of countries of the global South to alleviate the plight of those who suffer from the lack of access to clean drinking water. This activity is part of the “social responsibility” policy of the company and won several awards. But P&G does not tell other less glorious stories, in which it is also involved; stories about water consumption and pollution on a large scale in the Global South from the places where P&G obtains its raw materials.

In 2014, P&G had a net profit of US$ 11 billion and it is not a coincidence (2). It is one of the leading manufacturers of disposable paper products such as napkins and tissues. Products are manufactured with wood fiber pulp from companies promoting monoculture plantations of eucalyptus, acacia or pine in the South. P&G is among the main customers of these companies who have their plantations as close as possible to the pulp mill. The result is: areas with tens or hundreds of thousands of hectares of monocultures. The main requirement to buy from these companies is that their tree plantations are certified, preferably by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). Today, the vast majority of tree plantation companies already have the FSC label and according to P&G, production is “sustainable” and the pulp purchase is therefore, “responsible”.

Communities directly affected by plantations in countries like Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia are concerned. People living this plantation reality, with trees growing faster and faster, see nothing “responsible” in them. On the contrary, they are astonished to hear that while they are left with little or no clean water to drink or for other domestic activities, companies say there is no impact on water because plantations are managed following strict “technical criteria” approved by an international standard. An article in this bulletin highlights the importance of water for traditional communities, especially for women, giving an idea of its importance, not only for consumption but also for their cultures and their spiritual wellbeing. Therefore, these populations suffer when they lose their water sources. And the suffering grows even more when the water that is still running - despite of the “thirst” of fast growing trees - is contaminated with pesticides used on the plantations. The health of workers and communities are at even more risk, along with local flora and fauna. Another article in this bulletin explains in detail the issues related to tree plantations on a large scale and water. It is unfortunate that certification schemes like the FSC, supported by NGOs, are able to produce and spread an idea of “sustainability”, which is accepted by millions of consumers and contrasts sharply with reality, silences the voice and makes communities that suffer and die due to lack of water and other impacts even more invisible.

But the water problem around P&G production does not end there. The factories that transform wood fiber into pulp for export are also large consumers of water, and they run 24-hour production days. A pulp mill with its chemical processing requires similar or higher water consumption than a city with over 1 million inhabitants and generally uses water for free. We are not only talking about the exported pulp, but about companies also “exporting” water, because for every ton of pulp there is less water for the local population and more pollution, as shown by the article on APP in Indonesia in this bulletin. The same applies to other production chains in the Global South attached to agribusiness which ends up with products in supermarkets in the Global North, such as meat, fruits and vegetables, which also require huge amounts of water in all production and processing steps.

An example of another problem recently denounced by the South African Water Caucus (SAWC), a coalition of civil society that monitors water issues in South Africa, is the growing pollution of the country's rivers with toxic chemicals used in pulp production and that are present in the disposable paper ending up at the dump. This shows the perverse side of stimulating consumption by companies like P&G in the so-called “new markets” such as the growing urban centers in countries of the Global South. Often these centers lack properly functioning waste collection systems. River pollution is evident in those countries, and yet even more serious to jeopardize the health of more people dependent on the direct collection of water from rivers for their consumption. (3)

There is an interconnected two-way response to the crisis of water shortage and pollution in the countries of the global South. On the one hand, the trend of privatization of water and water treatment companies, as part of the “recipe” given by international bodies like the World Bank and the IMF to many governments especially in the global South has been expanding for years. Behind a discourse promising a more “efficient” management, there is a hidden interest of creating more business opportunities for the corporate sector. On the other hand, this trend is a precursor to a broader one: the growing view that water needs to be "financialized". Financial capital market companies identify a great business opportunity in water, as it is essential for people and for productive activities, but is increasingly scarce. Therefore, one of the articles in this bulletin deals with this topic.

Privatization, commodification and financialization of water are increasing worldwide, as is the number of currently one billion people without access to safe drinking water. A recent FAO report on water consumption in the world stated that the problem of intensification of industrial activities will further increase consumption and water pollution. But FAO stressed industrial agriculture - industrial tree plantations may be included within this category- as the main current and future consumer - and polluter – of water in the coming decades (4). Therefore, if we want to “save lives”, as P&G says, today and in the future, it is necessary not to “certify” but to change the current model of production and consumption. This model is “thirsty” and it is the principal user and polluter of water in the world - and puts much effort in expanding even further.

An important step, to which we hope to contribute with this bulletin, is to not tire of making visible the real impact of this model on populations, because big companies benefiting mostly from it are trying to make those impacts systematically invisible.

We also hope that this bulletin will inspire more people to come together to struggle for clean water for everyone, a struggle now being carried forward in many parts of the world. Privatizing and take-over what in many cultures in the world is a symbol of life has already generated strong popular reaction. Recall the victorious struggle some years ago of the people of Cochabamba, Bolivia, to reverse the privatization of water. A more recent example comes from Jakarta, Indonesia. In March this year, after years of protests, a decision by the country's institutional court cancelled the contract with two companies that managed the water supply of the city since 1998, due to allegations of mismanagement and corruption. The court decision opens the way for the re-municipalization of the system. (5)

Thus, the capitalist economic model, by which capital accumulation is linked to the increasing control and capture of cheap inputs or “natural resources”, is also translated into a massive theft of water. Water, however, as symbol of life, connects many struggles in defence of territories. Therefore, it is also an element of strength and hope against a model of production and consumption that is preying on forests, territories and their networks of life, including the people who live and depend on forests.

- http://www.pg.com/en_UK/sustainability/social-responsibility/children-safe-drinking-water.shtml

- http://www.marketwatch.com/investing/stock/pg/financials

- https://www.facebook.com/GeaSphere?fref=nf

- FAO: Towards a Water and Food Secure Future,

- http://www.fao.org/nr/water/docs/FAO_WWC_white_paper_web.pdf

- http://news.mongabay.com/2015/0417-jacobson-water-two-court-rulings.html