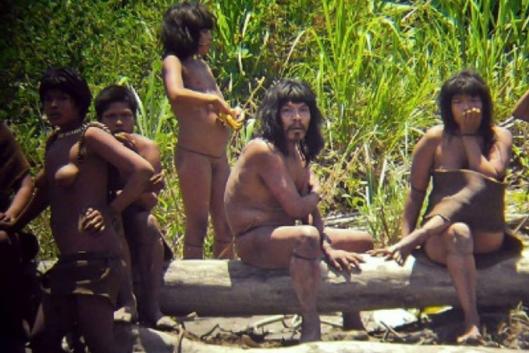

Photo: Mashco Piro indigenous peoples in the Madre de Dios reserve - By Diego Cortijo - Sociedad Geográfica Española, 2011. Source: Pueblos Indígenas en aislamiento voluntario y contacto inicial, IWGIA – IPES – 2012

The Peruvian Amazon and adjacent areas, across international borders, are inhabited by numerous indigenous peoples or segments of indigenous peoples in isolation. Their languages have been classified as primarily forming part of two linguistic families: Arawak and Pano. There are also numerous groups in the vast area made up of the headwaters of the Tahuamanu, Yaco, Chandless, Las Piedras, Mishagua, Inuya, Sepahua and Mapuya Rivers, to the southeast, who have yet to be identified. In addition, recent studies indicate the presence of groups possibly forming part of the Záparo and Huaorani linguistic families in Loreto, near the border with Ecuador, and other unidentified groups to the south of Madre de Dios, around the Bolivian border.

Information on their existence is mainly based on the testimonies of members of these same peoples who are now living in initial contact, and of indigenous and non-indigenous inhabitants of areas neighbouring their territories, who either see them or find traces of their presence during hunting or fishing trips. These traces include homes, remnants of fires, food, clothing, utensils, arrows, roads, branches blocking the path as a warning to stay out of their territories, footprints, and others. Oil company workers, loggers, hunters, fishers, missionaries, park rangers in protected natural areas, anthropologists, military border post staff and adventurers have also been witnesses to their presence.

Historical and ethnographic sources provide accounts of the withdrawal of segments of numerous Amazon indigenous peoples to remote areas of their territories or neighbouring areas, often in situations of extreme violence, after they have put up fierce resistance to the presence and attacks of outsiders. Clashes such as these can leave their populations decimated or seriously diminished.

Source: “Perú, despojo territorial,conflicto social y exterminio”, Beatriz Huertas Castillo, in “Pueblos Indígenas en aislamiento voluntario y contacto inicial”, IWGIA – IPES – 2012,http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/0603_aislados_contacto_inicial.pdf

Peoples in isolation in reservesPeoples in isolation, peoples with rightsThe rights of indigenous peoples in isolation are recognized in the international legal framework, although they have only received attention in recent years. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted on September 13, 2007, guarantees the right of indigenous peoples “to live in freedom … as distinct peoples” (Article 7) and obliges states to provide effective mechanisms for the prevention of and redress for “[a]ny action which has the aim or effect of depriving them of their integrity as distinct peoples, or of their cultural values or ethnic identities” and “[a]ny form of forced assimilation or integration” (Article 8.2). These rights, which apply to indigenous peoples in general, also apply by definition to indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation in particular.

Within the inter-American system, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States, has addressed the subject of the rights of isolated indigenous peoples through its various mechanisms. The IACHR has granted precautionary measures (PM) for the protection of indigenous peoples in isolation that include PM 91-06 on the Tagaeri and Taromenani indigenous peoples of Ecuador and PM 262-05 on the Mashco Piro, Yora and Amahuaca indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation in Peru.

Unlike other subjects of rights, indigenous peoples in isolation, by definition, cannot advocate for their own rights before national or international bodies. As a result, the protection of their lives and cultures is of particular importance for the inter-American human rights system.

The challenges and threats tend to be the same: the gradual but persistent invasion of their territories, the legal and illegal exploitation of the natural resources found there (from the era of the rubber boom to the exotic timber, hydrocarbons and minerals extracted today), and the diseases and epidemics that these activities bring with them.

Spreading information on indigenous peoples in isolation and raising awareness of their situation and their rights is the responsibility of all of us who work in defence of human rights.

Beatriz Huertas Castillo, IWGIA,http://www.iwgia.org/iwgia_files_publications_files/0603_aislados_contacto_inicial.pdf

To learn about the situation of indigenous peoples in isolation in reserves in Peru, we talked with Daniel Rodríguez, David Hill and Alejandro Chino Mori, who spoke from their experiences working on the Madre de Dios Reserve, the Nahua Kugapakori Reserve, and the Isconahua and Murunahua Reserves, respectively.

* Peruvian policies on indigenous peoples in isolation

Daniel Rodríguez, who has worked for the Native Federation of the Madre de Dios River and Tributaries (FENAMAD), said that the adoption in 2006 of a law to provide protection for indigenous peoples in isolation and initial contact implies legal recognition of the rights of these peoples and of their vulnerability, as well as establishing the state’s obligation to protect them.

David Hill of the Forest Peoples Programme, who has worked as a consultant at the Nahua Kugapakori Reserve, spoke to us about the five intangible “Territorial Reserves” created for these peoples, which comprise a total of 2.8 million hectares. While these indigenous reserves are an interesting initiative, and constituted the legal foundations for the development of special health policies, they basically emerged from the indigenous movement, which pushed for the adoption of legislation through studies and pressure, said Daniel. David agreed that state policy for the protection of isolated peoples is weak and is essentially driven by civil society.

In the meantime, the definition of the territories leaves open a legal loophole that permits the extraction of natural resources in the territories of isolated indigenous peoples for cases of “national interest”. This creates a legal ambiguity that leads to contradictions between the obligation to protect isolated peoples and the promotion of extraction-based development policies in the territories, namely oil and gas drilling and other “mega projects” in the Amazon.

As an example, David referred to “the recent report by the Ministry of Culture on the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the expansion of the Camisea gas project in the Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti Reserve which stated it could ‘devastate’ or make ‘extinct’ three of the indigenous peoples living there. That report disappeared from the public sphere within a few hours, was annulled a week later, and is now being re-written, and in the meantime various Ministry personnel ‘resigned.’ That just shows how seriously Peru’s current administration takes these issues!”

Daniel noted that a number of different groups of isolated people are currently becoming increasingly less “invisible” in certain sectors of the Amazon. Their growing proximity to others is interpreted by some as a change in their desire to remain isolated, an expression of their intention to “come out” and interact. This makes the work of protecting the rights of these people even more difficult, and highlights the urgent need to step up the minimal territorial protection efforts carried out until now.

For his part, Alejandro Chino Mori, a legal advisor on Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation at the Ucayali AIDESEP Regional Organization (ORAU), a branch of the Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP), believes that in Peru “there is no clear policy defined by the state and specifically by the successive governments in power to address indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation and initial contact. The ongoing struggle of our indigenous organization AIDESEP and its regional branches like ORAU has achieved some advances so that the collective and individual rights of these people are at least respected in one way or another, but they are still not guaranteed, and they remain vulnerable.”

* Number of groups of peoples in isolation

International specialists agreed on an estimate of 20 of these groups in Peru around 2005. Currently there are considered to be 15 to 20 groups comprising a total of 1,000 people from various linguistic families, primarily Pano and Arawak, but also Záparo and Huaorani, as well as others that are unknown.

The majority of members of some of these groups have established relations with national society, but some have chosen not to establish contact, such as the Matsigenka, Asháninka and Cacataibo. There are peoples with these characteristics in north and central Peru, but most of them are in the southeast of the country. Alejandro told us about the peoples who have been identified and live in the following territorial reserves: in the Mashco-Piro Reserve, the Mascho-Piro, Mastanahua and Chitonahua peoples; in the Murunahua Reserve, the Chitonahua and Mashco-Piro; and in the Isconahua Reserve, the Isconahua and Remo peoples.

* Are the existing reserves sufficient?

David answered categorically: “Absolutely not. As I’ve already said, the existing five reserves have never been properly protected, nor do they even cover all of the areas inhabited by the isolated peoples. The Madre de Dios Reserve is one example. As a result, they mean little or nothing in practice. In addition, there are the five proposed reserves which have still not been established, as well as PIAV [indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation] who live in areas where there are neither reserves nor proposed reserves.”

Alejandro concurs that the reserves for peoples in isolation are not sufficient “because their ancestral territories extend beyond the areas demarcated, for one simple reason: for them there are no set limits or borders for their movements and travels.”

Daniel also stressed, “Their relationship with their territories is dynamic and fluid. The creation of reserves with fixed borders does not align with the logic of these peoples, and particularly if they are subject to variable pressures and ecological and climate changes.”

* The situation of isolated indigenous peoples who are not in reserves

While specific realities vary greatly both between the different groups of people in isolation living in reserves and those living outside of them, Daniel noted that in general terms, these two situations do not differ a great deal, since the protection provided within the reserves is not as effective as it should be. Logically, the location of a reserve within a national park, for example, changes things, since on the one hand, there are more effective measures to keep people from moving too close and to prevent contact, but on the other hand, the objectives of these areas also include activities like tourism and scientific research, which limit the exercise of the rights of isolated peoples.

Alejandro commented that for isolated indigenous peoples who are not in reserves, AIDESEP has submitted formal proposals to the state for their recognition.

* Reserves in the process of demarcation

Several years ago, indigenous organizations, backed by other civil society organizations, proposed the creation of five reserves in addition to those already established.

The Multi-Sectorial Commission created by Law 28736, explained Alejandro, is responsible for discussing the demarcation of these new reserves. These have already received a favourable technical opinion, which needs to be approved by this commission and submitted to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers for its approval.

“In a letter to AIDESEP earlier this year,” said David, “the Ministry of Culture revealed its support for the five proposed reserves. These proposals were expected to be discussed by a cross-government commission in Lima in August, but the meeting was postponed and has been re-scheduled for next month.

“What will happen remains to be seen. Remember, since the resignations at the Ministry over the EIA for ‘Lot 88’, the personnel there now is very different. But this whole process, which is taking years and has been driven by civil society, particularly the indigenous organizations, is really quite embarrassing for the Peruvian government. Or at least, it should be. It demonstrates very clearly, once again, how little it cares about the PIAV – or, to put it another way, how little it cares for the human rights of some of the country’s most vulnerable citizens.”

* Free, prior and informed consent and indigenous peoples in isolation

UN guidelines on the protection of isolated peoples recognize isolation as an expression of political will. Therefore, the right to not participate must be respected as such, and particularly in view of the immunological vulnerability of these peoples. Peru is obliged to abide by international law, as well as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ interpretation of the American Convention on Human Rights, which the country signed in 1978.

According to David, “What it means – or rather, what it should mean – is that Peru can’t grant concessions to oil and gas companies, or to anyone else, in regions where there are isolated peoples. Obviously not. They are isolated peoples! They are in ‘voluntary isolation.’ They are not in contact with the State, and therefore their consent can’t have been obtained. However, that said, there is a danger here that this concept is manipulated and contact with the isolated peoples is sought or engineered in an attempt to comply with the law and/or make it appear their consent has been given. This would not only undermine the principles of free, prior and informed consent itself – how could any such people really be ‘informed’ about oil or gas operations on their territory? – but it could also be catastrophic, as I’ve already explained. As indigenous peoples, they also have the right to self-determination, recognized by international law. This means they have the right to live as they choose, which in this case is in ‘voluntary isolation.’ The Peruvian government should respect that, and, in doing so, it has the opportunity to set a progressive human rights example to other countries where there are isolated peoples too.”

On this basis, said Daniel, “it is necessary to adopt decisions on each situation in particular, as in the case of the Mashco Piro group in Alto Madre de Dios, which has become increasingly visible since May 2011 and has given signs of wanting to establish communication with others. Although in this type of case it is not possible to deny the possibility of a dialectic exchange, there is a need for a process of reflection on the way and the conditions in which a process of dialogue would be initiated. This type of process to define consensual strategies for interrelations has yet to be formally initiated, and there are various area in which it is very much needed.”

* New mapping technologies (Google Earth, GPS): benefits or threats for isolated peoples?

Alejandro commented that, as working tools, these new technologies make it possible to more precisely define the areas where isolated peoples live and pinpoint the exact spots where they have been sighted or where evidence of their presence has been found.

Daniel commented on his own experience: “This is a key point. Images of isolated indigenous peoples accompanied by their location have become increasingly frequent in the media. Politically, these materials play a very important role, because in Peru, the existence of these peoples has been publicly and repeatedly questioned by certain sectors of the government. The struggle for the rights of these people has been largely focused on demonstrating their existence nationally and globally. One of the clearest cases is the dissemination by FUNAI [the Brazilian government agency for indigenous affairs] of aerial photos of a group of isolated indigenous people on the border between Peru and Brazil in 2008.

“It is also necessary to reflect on the use of these images: publicly exposing a group on a repeated basis in the media entails risks because of the ‘pull effect’ it can have on third parties, and it also raises ethical issues around the use of their image. In the specific case of the Mashco Piro group in Alto Madre de Dios, this exposure has not translated into significant changes in public policies for their protection.”

The situation in the Madre de Dios Reserve

– in conversation with Daniel Rodríguez –* What are the characteristics of the Madre de Dios Reserve, including the area it covers in relation to existing groups of PIAV?

“The Madre de Dios Reserve was a solution for the protection of the territory of isolated peoples in the north of the department Madre de Dios, adopted during a politically and economically turbulent time in the region.

“A consensus was reached for the delimitation of the area without taking into account the information available on the territory actually inhabited by the isolated groups, and so the eastern border separating the reserve from the area of forest concessions is artificial.

“The presence of isolated peoples outside the reserve is a problem that has become more accentuated in recent years and has created complex challenges, because the territories used by these peoples overlap with the rights of other indigenous peoples who inhabit the area.

“At the same time, the Madre de Dios Reserve is paradigmatic model for the protection of rights in Peru – particularly because of the notable and sustained absence of a state presence and the predominant role of civil society, primarily of the regional indigenous organization FENAMAD, in the implementation of protection policies. FENAMAD played a catalytic role in the creation of the reserve in 2002, which continues through its work in the protection of the territory and early warning efforts, in coordination with neighbouring indigenous communities, particularly in the Las Piedras River basin.

“In recent years the state, through the agency responsible for policies on the protection of isolated peoples, INDEPA, has expressed interest in taking over the protection of the reserve. These initiatives have not moved beyond declarations and have not yielded any practical results. Moreover, there has been a tendency to not recognize the work and the role of indigenous organizations and communities, which has exacerbated conflicts between indigenous organizations and the state over the legitimate representation of the interests of isolated peoples.

* What are the threats to PIAV in these regions and what are the current trends? Are these threats the same as when the reserves were created, or are there others now?

“There have been significant changes in the Madre de Dios Reserve. The nature of the threats is not as visible as at the time of its creation and in subsequent years, in the sense that there is no longer a massive presence of illegal loggers within the reserve – although there are still areas where illegal logging continues. Logging activity has been largely formalized and is carried out around the reserve. These big companies are working in areas that directly border on the reserve and are occupied by isolated peoples. Many of these companies are certified and have declared an interest in contributing to the protection of the reserve, but we have information that they have continued to extract timber from areas of their concessions where the presence of isolated peoples has been recorded, which poses a risk to the lives of their workers and the indigenous peoples. This is a complex situation. The companies have rights that were granted to them by the state, but it should be kept in mind that the granting of these concessions during the creation of the reserve resulted from political negotiation and not from a decision based on the available information on the actual use of the territory by isolated peoples.

“In the meantime, there are a series of issues that are less tangible that affect isolated peoples, such as the complex relations between isolated peoples and their neighbours, or ecological and climate changes. In the case of the Macopiro, they move around within vast areas of land on the basis of resources that are available in certain places, such as rivers, where they go during dry periods in search of turtle eggs and other game. Severe droughts that lengthen the dry summer season and dry up the rivers lead these isolated peoples to spend more time on the banks of the rivers, without returning to higher areas, leading to encounters on the beaches, and the consequences these have. The effects of climate change are also altering hunting patterns.

“There is no doubt that development projects in nearby areas have had a major impact on the mobility of isolated indigenous peoples, while it has also become evident that there are outsiders passing through the reserve, including individuals involved in drug trafficking.”

The situation on the Nahua Kugapakori Reserve

– in conversation with David Hill –* What are the characteristics of the Nahua Kugapakori Reserve, including the area it covers in relation to existing groups of PIAV?

“This reserve was established in 1990 and then given greater legal protection by a Supreme Decree in 2003 which changed its title to include, as well as the Kugapakori and the Nahua, the Nanti and ‘others.’ It stretches for over 450,000 hectares and sits between the River Urubamba, one of the principal sources of the River Amazon, and the Manu National Park, described by UNESCO as the most biodiverse place on the planet. However, like the other four reserves, this one has never been properly protected. In fact, it’s a particularly tragic irony that this reserve has the ‘best’ legal protection of all the existing reserves and even has a few government-funded control posts, but it is actually the least protected in practice.

“In 2000 the Peruvian government signed a contract with the Camisea consortium to operate in a concession called ‘Lot 88’, almost 75% of which is superimposed over the reserve and which almost cuts it entirely in half. Pluspetrol has been there ever since, exploring for gas, drilling and pumping, and it now plans to expand its operations further north, east and south into the reserve, which is what prompted an appeal to the United Nations in January this year by national indigenous organization AIDESEP, regional indigenous organizations COMARU and ORAU, and the Forest Peoples Programme, for whom I’m working as a consultant. These expansion plans include drilling wells and conducting 2D and 3D seismic tests in areas used by the PIAV: e.g. in the south-east and north-east of Lot 88 in the headwaters of the River Cashiriari and River Serjali. Pluspetrol openly acknowledges this in its EIA. It states that the PIAV are very vulnerable, that contact is ‘probable’, and that, in general, contact can lead to ‘massive deaths.’ Indeed, the EIA also acknowledges that operations by Pluspetrol in 2002 and 2003 led to forced contact with some Matsigenka in ‘voluntary isolation’, and quotes Peruvian anthropologist Beatriz Huertas Castillo that the Camisea project has forced contact with some of the Nanti too.”

* What are the threats to PIAV in these regions and what are the current trends?

“The demand for oil is one of the biggest threats. Perenco, Repsol and Subandean operate in ‘Lot 67’, ‘Lot 39’ and ‘Lot 121’ in northern Peru near the Ecuadorian border, and Pacific Rubiales is in ‘Lot 137’ in northern Peru near the border with Brazil. All of these concessions overlap areas inhabited by the PIAV and proposed reserves. These operations are at different stages and therefore the threats vary.

“Perenco is sitting on deposits declared commercially viable back in December 2006 and it had been hoping to start pumping by July this year, and the kind of infrastructure this requires – platforms, wells and eventually a pipeline – means that the company intends to remain there, in PIAV territory, for many years. Repsol, by contrast, has announced a series of finds since 2005, but is continuing to explore, by drilling wells and conducting more seismic tests, while Pacific Rubiales only started its seismic tests very recently. Of course, conducting such tests doesn’t mean that the company will spend as long in any one area as it would if it discovered deposits it intended to exploit, but as Peru’s Defensoría del Pueblo (Ombudsperson) has acknowledged, it is the exploration stage that is most likely to lead to contact because of the way the seismic teams move about. As has been emphasized over and over again, any kind of contact – and I mean ANY – between the PIAV and company workers could be catastrophic because of their lack of immunological defences and the fact that even colds and flu, if transmitted, can easily kill them. Of course, that’s to say nothing of what happens when the oil is spilled. Look at the River Corrientes in northern Peru to see how devastating that can be.

“Gas is another big threat, as I’ve already made clear. Not only in ‘Lot 88’, though. It’s also possible the government will establish another concession, ‘Lot Fitzcarrald’, which would beimmediately to the east of ‘Lot 88’ and immediately to the far west of Manu National Park and would completely split the Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti Reserve into two. Peru’s Energy Minister played down ‘Lot Fitzcarrald’ at a hearing in Peru’s Congress in April, following considerable media interest and some civil society opposition, and some people appear to think it’s no more than a myth or a fantasy, but the threat remains. No doubt about it.”

* Are there other threats?

“Certainly. The reserves have all been invaded repeatedly by loggers, and then there are Christian missionaries, drug traffickers, occasional tourists and even film-makers seeking exotic subjects. The missionaries can be particularly dangerous because they actually want to make contact with the PIAV, unlike the loggers, drug traffickers and oil and gas companies, etc., for whom they’re either simply inconvenient, or a potential threat to life, or, for the latter at least, a potential public relations problem. The loggers can be particularly dangerous too. Despite efforts to control logging by establishing concessions, many of them overlap unprotected PIAV territories, while illegal logging outside of these concessions is still rampant in remote tributaries where valuable hardwoods remain. Of course, all this is completely unregulated, and the loggers, unlike the oil and gas companies, often carry guns. I’ve seen them myself, armed, boating upriver into one of the reserves. No one there to stop them. Sometimes you hear reports of skirmishes and loggers being wounded, or even killed, by the PIAV, but you never hear how many indigenous people died.”

* Are these threats the same as when the reserves were created, or are there others now?

“I think that most of the threats remain the same. However, while the principal threat, say, 10 years ago, was from logging, today it is most clearly from oil and gas. Estimates vary, but the percentage of the Peruvian Amazon currently overlapped by oil and gas concessions is very high. Just look at a map! That said, there is a whole new threat that is, in the long-term, potentially more serious than any of the others. The 2006 law I mentioned earlier? One of the things that law does is create a new legal category for the PIAV called ‘Indigenous Reserve’ where, according to the law’s Article 5, Clause C, natural resources can be exploited if deemed to be in the ‘public necessity.’ This is a serious loophole that, as I said before, ultimately makes a charade of the rest of the law. Now there is, already in process, a plan to turn all five ‘Territorial Reserves’ into ‘Indigenous Reserves’, thereby transforming them from supposedly ‘intangible’ to, well, tangible. Exploitable. Not, sadly, that this ‘intangibility’ has meant very much anyway in the case of the Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti Reserve!”