Background

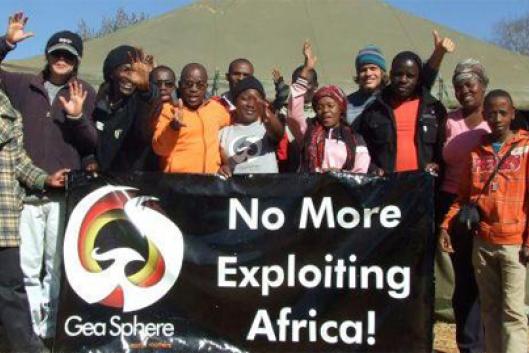

Much has been written about the plunder of biodiversity and other natural resources from Africa, in particular where negative social, economic and environmental impacts have resulted; as with indiscriminate clear-cut logging of forests, ruthless mineral extraction, and the conversion of community land into industrial plantations. But despite substantial political change over the past 100 years, Africa’s unequal economic relationship with the global North remains.

Although current methods to siphon Africa’s wealth might appear different to those used in the past, the negative effects of resource extraction remain. Although African countries achieved political freedom at ‘independence’, many are still controlled by foreign powers, but not only by Britain and other countries in Europe. Demand for Africa’s resources now also comes from North America and Asia.

During early colonial times, crude extraction of precious stones, ivory, animal hides and ostrich feathers was glorified. Local people were exploited for local knowledge, food and labour, including through enslavement; with missionaries, traders and explorers paying the bare minimum, mainly with trinkets: mirrors, bangles and beads, but also with guns and alcohol. When European governments learned that Africa’s mineral deposits and land were valuable prizes, military incursion became the favoured appropriation method. The first wave of infrastructure: roads and railways to move soldiers and equipment, was later used to export their spoils. Over time, an extensive network of roads, railways and ports was constructed to facilitate extraction and transportation, mainly to European markets.

This brought a new phase in Africa’s exploitation. Foreign countries started to accumulate capital in the form of natural resources and built infrastructure in the colonised territories, but profits went to overseas banks; to be used to help finance further subjugation. This system of self-sustaining resource extraction has impoverished Africans till today, even though colonial nations have been replaced by a more powerful but insidious force in the form of commercial banks that are protected by the governments of their countries. This also provides a convenient ‘private sector’ buffer to protect those working behind the scenes to orchestrate land grabs, timber and mineral extraction, or the primary industrial processing of their spoils, which also depends on access to cheap African labour; and lax enforcement of environmental and worker health protection laws.

Thus, although the political landscape may have changed, the natural wealth that exists in Africa, or wealth that has been created in Africa by local communities, is still accumulated mainly in the form of financial capital held in countries elsewhere in the world.

In the present

The lure of so-called ‘Foreign Direct Investment’, now leads many African leaders and political elites to encourage the extraction of an even wider range of resources in the form of ‘raw materials’ needed to help sustain industrialised economies in the North. Also a complex array of international financial institutions (IFIs) works in partnership to squeeze more blood out of the African stone. In recent times, private ‘investors’ have been over-shadowed by multilateral financial institutions, including the European Investment Bank (EIB), the World Bank (WB), and its offshoot, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which still take their cue from the governments that fund them.

Lurking in the background, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) appears to exert a disproportionately powerful influence over the economic policy choices of many African countries; encouraging increased exploitation of their natural resources in pursuit of crude economic growth. The IMF also helps to influence countries with low ‘Gross Domestic Product’, or GDP, to borrow money for transport and other infrastructure to aid movement and export of basic commodities, especially unbeneficiated minerals and timber, but does little to support projects run by local communities. The IMF also tries to influence where and how its financial assistance can be spent, as in Kenya (1).

The IMF promoted the concept of continuous ‘economic growth’ based on increasing national GDP, which is deficient in terms of achieving sustainable local development that benefits local citizens instead of multi-national corporations. It relies on the short-term exploitation and consumption of limited or finite resources such as water, to boost economic activity. This leads to natural resources being depleted rapidly, and reduces local beneficiation and employment opportunities. A case in point is how Kenya appears to have been influenced by the IMF to take steps to “rehabilitate” its “Water Towers”, leading to local communities and indigenous peoples being removed from parts of the Mau Forest Complex, and more recently forced evictions of the Sengwer people in the Cherangany Hills area. At the same time the Kenya Forest Service has plans to establish industrial timber plantations in these areas that will use more water than the subsistence agriculture that they replace (2).

Another threat to the economic independence of African countries is the United Nations scheme to ‘save the climate’ known as REDD+ or ‘Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation’. There is little doubt that REDD+ was a contributing factor in the evictions of the Sengwer due to possible cash payments for carbon offset credits earned through so-called ‘sustainable forest management’. This is linked to the plantation plans described above, converting forest reserve lands into alien pine monocultures that cause far greater damage to biodiversity, soils and water bodies; and ultimately release even more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than small-scale farming (3).

In many cases, African states still have strong cultural and economic ties to the colonial nations that previously ruled them. For example the relationship between France and its former colonies in West Africa; and similarly ongoing relations between Portugal and its one–time African provinces, Angola and Mocambique. But no matter what historical connections there might be, the main interest of former colonial masters remains the same: to maintain influence over African governments and African people in order to secure ownership or control of resources. Development aid (including food aid) is a powerful tool in this regard, as it can be used to create economic dependency through increasing debt and reliance on handouts. It also ensures that a smaller share of benefits go to legitimate African owners - local communities and indigenous peoples - who have preserved the forests and other ecosystemsfrom which resources are extracted.

In order to thwart popular local resistance to the theft of African resources, agents of neo-colonial powers often employ military tactics, which require costly equipment and weapons to destabilise countries. Using local groups to help mining and extractive corporations to assert and maintain their control over forest or mineral resources is probably more the rule than the exception. To illustrate this point, there have recently been armed conflicts linked to resource access in several countries: South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Uganda, Somalia, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In almost every case, military expertise and hardware has come from outside the affected country, meaning that these must either be supplied or at least paid for by a foreign entity with an interest in obtaining access to land or mineral resources in such African countries. Funding for ‘military infrastructure’ has largely replaced using foreign mercenaries, but the same basic approach remains: to divide and to rule by exploiting local conflicts.

A new form of extraction

Africa is perceived as a gullible consumer market for over-priced but low quality imports. Whether for canned sugar-water, genetically engineered seeds, junk food or cheap clothing, the business world sees opportunities in Africa! For multinational corporations seeking to increase their sales and profits, or to pre-empt local business initiatives that might threaten their dominance in global markets, Africa is seen to be ripe for the plucking.

Countries such as South Africa have paid massive amounts of money for over-priced military equipment supposedly to protect themselves from perceived or potential enemies. Often however, they lack the means to properly maintain new toys of ‘mass deterrence’. Apart from South Africa, few African countries have the capacity to manufacture their own weapons, making Africa a ‘sitting duck’ from the point of view of foreign countries wanting to sell their surplus or out-dated military equipment. It is likely that many arms transactions do not involve payments in hard cash, which is generally in short supply, so some African governments might end up offering heavily discounted mining concessions or business rights as payment. When ill-disciplined soldiers hold loaded weapons, much can and will go wrong (4).

The false philosophy that motivates this kind of greed and ambition rests upon the crazy notion that there can be never-ending growth in production and consumption, driven by seemingly infinite expansion of the world’s human population. The number of people is projected to pass 9 billion by mid century, seemingly to answer the profit prayers of big business. But using simple logic and being aware that we occupy a planet with a rapidly diminishing area of habitable land, declining natural resources, ecosystems in danger of collapse and accelerating climate change, everyone should understand that a radical change in human attitudes and behaviour is needed. However for this to be possible the global economic system must also be changed from rampant capitalism to a system that respects the rights of Nature and of people.

The perverse effects of infrastructure

The establishment of ‘hard’ infrastructure comes about either as a response to a specific need, e.g. railroads for transporting minerals from inland mines to coastal harbours, or as a risk-based initiative that assumes that demand for certain services will develop at an anticipated rate and that will eventually justify the cost of its construction, e.g. building a new highway for which there is insufficient demand at the present time, but that could possibly become fully utilised at some uncertain point in the future. In South Africa there are some prime examples of ‘white elephants’ built for their ‘show-off value’ such as the over-priced soccer stadia built ahead of the 2010 Soccer World Cup.

The King Shaka international airport at Durban was built mainly to accommodate a brief rush of extra passengers visiting Durban during the World Cup, but is now operating well below its potential capacity, while the perfectly serviceable and recently upgraded old Durban airport stands unused. Apart from an extravagant government scheme to turn the airport into a ‘dug-out’ container port at some future time, it will probably remain a drain on public resources into the future. Given the urgent need to address climate change by reducing emissions from fossil fuels, both the new international airport and the proposed new container port stand out as bad ideas, yet the government-subsidised South African Airways is planning to enlarge its fleet of large jet planes!

An important aspect of any large infrastructure project is that it should serve an existing local need from the onset, and not be built merely to achieve some other imagined or desired purpose; and it should be able to generate enough income from the start, so as to be able to pay off the loans taken to pay for its construction. The above examples of superfluous expenditure are not the only ones in Africa that have wasted scarce financial resources, but it must be emphasised that irrational decisions to borrow large amounts of money to build unnecessary infrastructure will surely increase a country’s debt burden and therefore its credit-worthiness.

Throughout Africa, ambitious large-scale infrastructure projects are being built or planned, including massive dams on the Congo and Nile Rivers, highways, railroads, harbours and power stations, but will these improve livelihoods for African communities, or rather help to increase resource extraction, environmental damage, and human suffering?

Notes:

(2) http://www.imfbookstore.org/ProdDetails.asp?ID=9781455207589&PG=1&Type=BL

(3) http://www.no-redd-africa.org/images/pdf/sengwernranletter12march2014.pdf

(4) http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/dr-congo-arms-supplies-fuelling-unlawful-killings-and-rape-2012-06-12 - Chasing bullets in the DRChttp://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/chasing-bullets-drc

By Wally Menne, The Timberwatch Coalition (www.timberwatch.org)

Email: plantnet@iafrica.com