The region typically known as “India’s North East” or also referred to as just “North East” is linked tenuously with mainland India by a roughly 20 kilometer-wide land bridge, and surrounded by Nepal, Bhutan, China, Myanmar and Bangladesh. There are over 200 indigenous and tribal communities living in this region, most of whom share similarities in culture, food, clothing, economy and polity, and evolved diverse laws and institutions specific to each tribe.

Despite increasing urbanization, particularly in the capital cities, community life defined largely by nature continues. Mountains, forest, and rivers shape their lives. In parallel, the state and corporations continue to push their ‘development’ agenda, much more now as global capital and extractive industries are moving into ever remote areas. In the context of this advancing 'development' agenda, the meaning and uses of forest are being re-defined.

Forest cover in statistics exceed 70-80 per cent of most states in the region. It’s one of the few remaining ecologically diverse and intact regions on this earth. Within these forests are the communities that thrive. They ‘own’ and ‘control’ these forest areas under community control. States do not have direct authorities in these community forests, except for state reserves or protected areas. For example, Manipur state has 77 per cent of its total area under forest but out of these only about 7 per cent is under the state government control; for the remaining forest land, direct control rests with the communities. However, in Assam, large tracks of intact forest were destroyed when British colonial agents brought in commercial tea plantations. Today tea plantations occupy 312,210 hectares in Assam, believed to be the single largest tea-growing region in the world.

Commercial cash crop plantations, especially rubber, while not new to the region, are increasingly eating into intact forest areas. Tea and coffee plantations are expanding into the mountain forest. In Tripura, forest destruction has already begun to make way for up to 100,000 hectares of additional rubber plantations. Tripura already is the second largest natural rubber producer in India. The expansion is taking place on tribal forest land under local authorities. Rubber plantations are being expanded into the states of Arunachal and Nagaland, too.

Another industrial plantation expansion is oil palm in Mizoram. The government of Mizoram is aiming to increase the area of oil palm plantations to around 150,000 hectares.

In Meghalaya, environmental impacts, and particularly, forest destruction of coal and limestone mining have been well documented and further coal mining has been banned by the Supreme Court. (1) The advance of commercial plantations and large-scale mining on community-controlled land also point to the changing nature of and pressure on society/villages.

Laws and Institutions that govern forests in this region vary. Customary laws and institutions differs from one tribe to another, but they are community-oriented. Typically, village heads or council of the village and/or clan allocate forest land to a family for shifting (jhum) cultivation. If a plot is abandoned, the land goes back to the community. Selling of land is not permitted nor is community land traditionally inherited or transferred to individual ownership. However, both selling of land and transfer of land to individual ownership are encroaching as a result of both internal and external pressures. Nowadays, local tribal leaders are known to have given away land/forest through what is known as "no objection certificate" to commercial ventures that provide documentation of having passed environmental and other safeguards. In other cases, village councils have been withholding permits for mining –reassuring evidence that consent and self-determination do work for the future sometimes.

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 is a progressive national policy that seeks to redress the historical injustice done to the tribes and traditional dwellers of the forest. It has also been called the Forest Rights Act, the Tribal Rights Act, the Tribal Bill, and the Tribal Land Act (see WRM Bulletin 205). This Act, for the first time has, inter alia, recognised and vested the forest rights and occupation in the forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional dwellers who have been residing in such forest for generations but whose rights could not be recorded. Except for Assam and Tripura, the other six states of the North East have not implemented it with the argument that there is already community ownership of the forest and that there is a fear that external laws might later override the existing local authorities.

Factors that can deeply affect the forest in the region in the coming years include expansion of mining, dams, highways and railway expansion, infrastructure, expansion of commercial plantations, climate change related activities.

Coal mining is a critical issue in the states of Assam and Meghalaya. Due to its severe environmental impact, the National Green Tribunal of the Supreme Court has banned coal mining for now (1). An oil spill at the operations of the Oil and Natural and Gas Corporation (ONGC) in Wokha District of Nagaland has created massive devastation on forest and farmlands. (2) Local organizations have gone to the court for compensation and rehabilitation. There are existing proposals for oil mining in the states of Mizoram, Manipur and Arunachal. All of these proposals would result in forest areas being destroyed and diverted for other uses.

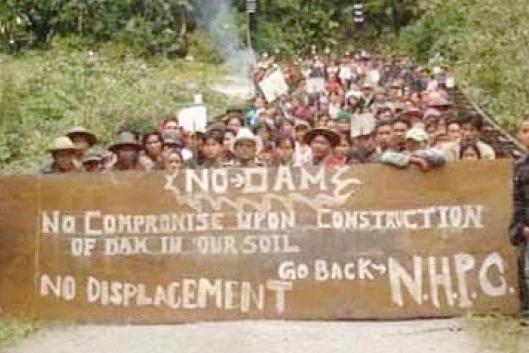

In addition, the government plans to construct more than 150 dams, most of which will be large-scale. In the state of Arunachal alone, the Government has entered into several Memorandums of Agreements for 127 dams in portions of 42 rivers with as many as 59 dam companies, aiming to generate 42,591 MW of electricity. All of these dams will submerge large tracks of dense and intact forest areas. In Manipur, the controversial Tipaimukh High Dam was ‘cancelled’; its construction would have submerged 22,777 hectares of forest land. Local opposition combined with national and international outcry facilitated this rare case of a dam being stopped that would have submerged a large area of forest and countless livelihoods linked with these forests.

Highways, railways and infrastructure are priorities in the government of India's plan to ‘unlock’ the region. 'Unlocking' of the culture and the ‘beauty’ of the region for tourism, 'unlocking' the forest for timber extraction, its carbon storage facility, traditional medicine etc, 'unlocking' for plundering of minerals and infrastructure to link India to the geopolitically and economically influential ASEAN region. Two key pieces of infrastructure, the Trans Asian Highway and the Trans Asian Railway are currently under construction. A major oil and gas grid that connects South Asia with South East Asia is being planned and a regional Energy Grid is already underway. All of these infrastructure developments will have direct implications on forest peoples' way of life and livelihoods and destroy large areas of forest.

Climate Change and Forest

While forest-dependent communities like those found throughout the North East lead some of the most low-carbon ways of life, climate change is already affecting their way of life and livelihoods. Those impacts are exacerbated by the implementation of two types of forest-related activities that are supposed to help mitigate global warming. One is restoring supposedly "degraded" land or ‘protecting’ existing forest as carbon stores or carbon sinks; the second type of activity is industrial biomass plantations for agrofuel or energy generation. The plantations created for these purposes - usually vast areas of monoculture plantations, owned and controlled by corporations - can hardly be considered as a forest by any stretch of imagination.

One of the architects of forest carbon projects in the North East is the World Bank. As part of its study ‘Natural Resources, Water and the Environment Nexus for Development and Growth in North East India’, (3) the background study ‘Carbon Finance and Forest Sector in North East India’ clearly supports and paves way for converting agricultural and forest land for more ‘profitable’ forest carbon projects. An additional backgrounder for the same study titled ‘Forest Sector Review of North East India’ also points to carbon capture programs in the region. With the Bank’s clear intention of intervening in the forest sector in the NE, it is likely that the NE Livelihoods Project of the World Bank will have substantial carbon related projects. If the Banks’ plan to involve the entire NE in this project, and if the carbon sinks are part of the project in each of the district components, the entire landscape and communities in the NE will be negatively affected by this false solution to the climate crisis.

The US-based Community Forestry International (CFI) started the Mawphlang REDD+ Project as the first pilot project in the region in 2011. (4) The Mawphlang REDD+ project is situated in the East Khasi Hills in the Meghalaya district, and is sometimes referred to as the ' Khasi Hills Community REDD+ Project' by CFI. The project area covers 15,217 hectares comprised of approximately 9,270 hectares of dense forests and 5,947 hectares of open forests in 2010. The forest included in the REDD+ project is an ancient sacred forest grove. CFI lists a number of local NGOs and entities as collaborators: the Bethany society, the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council, Planet Action and UK-based private Waterloo Foundation. The local Ka Synjuk Ki Hima Arliang Wah Umiam, Mawphlang Welfare Society is listed as project proponent alongside CFI. Waterloo Foundation provided GBP 100,000 in financial support to the project for 2011-12. According to the project document, the carbon rights for the forests included in the REDD+ project are with Ka Synjuk Ki Hima Arliang Wah Umiam, Mawphlang Welfare Society Federation. The Khasi Hills Community REDD Project was certified under Plan Vivo (Edinburgh, UK) standards in March 2013. In June 2013, 21,805 carbon offset certificates were issued in the Markit Registry, a private sector database that tracks the issuance of REDD+ credits. Project documents suggest that the project is entering its second implementation phase in 2017.

While the documents online contain all this information cited above, people on the ground who are real ‘owners’ of the forest does not know what REDD+ is. Many villagers used to grow crops on the hillocks. However, when the REDD+ project started, they had to look for other places to grow their crops. There is very little benefits to villagers from this REDD+ project.

Another new REDD+ project covering an area of 44,391 hectares is located in the Aizawl and Mamit districts of Mizoram. This new program is run jointly by the Indian Council of Forestry Research & Education (ICFRE), International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), Nepal and Agency for International Cooperation, Germany (GIZ). (5) As with the Mawphlang REDD+ project, villagers and office bearers of village councils have received little to no information about the REDD+ project, how it functions and its implications. In their documents, REDD+ projects are portrayed as a way out from Jhum cultivation and that these new forest carbon offset activities can take care of the financial needs of the villages. In two villages visited so far by this author, the existing forest have been conserved for many years under the initiative of the village prior to the arrival of the REDD+ project. . The carbon project has monetized and ‘taken over the forest’ from the villagers who have given tremendous hard work and voluntary commitment to protecting the forest long before the arrival of the REDD+ project. This is a new era of communities losing control over their forests to outside organisations.

The second type of activity promoted in the name of climate protection that has affected forests and peoples' livelihoods in the North East are agrofuel plantations, mostly jathropa. The Indian Government's Planning Commission set up committees to promote agrofuel plantations; they invested in product development, engineering studies, easing legal regulations, plantation specifications, marketing, etc In the North East, the joint venture company D1-Williamson Magor is the main promoter of Jatropha plantations. D1 Oils Trading Ltd.,U.K. was one of the first companies acquiring land for agrofuel production and Williamson Magor is the largest tea planter group of India. They had big expansion plans, not only for jatropha plantations in the North East but across Asian and African countries They announced plans for 100,000 hectares of jathropa plantations in the North East alone, and farmers and Jhumias (villagers practicing shifting cultivation) were lured with bank loans and buy-back guarantees. Like elsewhere, the jathropa plantation experiment seems to have failed, however, and the costs are born by the villagers left with expenses but no jathropa oil to sell and fields covered with the poisonous plant. Field visits showed abandoned farm and jhum lands covered with jathropa plants. What is most perplexing is how those villagers and communities least responsible for climate change are being requested to take up the key task of reducing their meagre carbon emissions. There are news that agrofuel expansion will be re-launched with new vigor. If these plans were to materialize, it would spell bad news for the forest and for local subsistence food production.

Ram Wangkheirakpam

Executive Director of Indigenous Perspectives, Imphal, Manipur

(1) An article on the Supreme Court decision banning coal mining in the NE of India is available at http://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/meghalaya-suspends-rathole-coal-mining-44432

(3) World Bank study 'Natural Resources, Water and the Environment Nexus for Development and Growth in North East India’; background study ‘Carbon Finance and Forest Sector in North East India’; and ‘Forest Sector Review of North East India'

(4) REDD+ in India, and India’s first REDD+ project: a critical examination. Report by Soumitra Ghosh. Available at http://www.redd-monitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/03_Mausam_Sept-2011.pdf ; summary and commentary by REDD-Monitor available at http://www.redd-monitor.org/2011/11/29/indias-first-redd-project-in-the-east-khasi-hills-when-you-say-that-i-need-permission-to-cut-my-own-tree-i-have-lost-my-right-to-my-land/

(5) Mizoram selected among others for REDD+ project http://www.mizoramtourism.org/mizoram-news/mizoram-selected-among-others-for-redd-project and ICFRE Initiatives on REDD+ , last 10 slides refer to the REDD+ project in Mizoram; available at: http://www.ignfa.gov.in/photogallery/documents/REDD-plus%20Cell/Modules%20for%20forest%20&%20Climate%20Change2016/Presentations/Resource%20Persons/TPSingh_IGNFA18Oct2016.pdf