Large conservationist NGOs have played a major role in turning REDD into the dominant forest policy worldwide. This mechanism was introduced in 2007, and the first wave of REDD projects and programmes was implemented from 2008 to 2013. Some of the promoters of REDD projects included these large NGOs, which benefit from receiving millions in grant money for ‘pilot projects’ and ‘capacity building’, as well as from selling carbon credits on the carbon market.

Evidence from the past two decades has confirmed that the early warnings about carbon offsetting in general, and about REDD in particular, have proven to be true. REDD projects have completely failed in their objective of reducing deforestation, and therefore have failed to mitigate climate change too (2). And yet a second, bigger wave of forest carbon projects and programmes has been underway since 2020, when the Paris Agreement came into effect.

Sub-national and national REDD programmes have received less attention than private REDD projects. These projects are referred to as “Jurisdictional REDD” or “government REDD”, and they cover a whole province or country. The World Bank's Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) is one of the major promoters of jurisdictional REDD. Its aim is to help countries in the global South get prepared to receive REDD payments, through a Readiness Fund; and then to reward them for reducing deforestation with so-called ‘results-based payments’ through a Carbon Fund.

Since it was launched in 2008, the FCPF has struggled to disburse the funds and to demonstrate results. Furthermore, in places where the FCPF has paid out money, many problems have appeared. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, the FCPF supported the PIREDD/Plateaux REDD+ Programme in the province of Mai-Ndombe. This WWF-run programme restricted communities' land use and caused conflicts (3). Problems also appeared in another jurisdictional REDD programme in Zambezia province in Mozambique, where the FCPF fully failed to achieve its main objective: to stop deforestation (4).

And yet, big conservationist NGOs like TNC refer to the FCPF as a “success” (5), not least of all because of the key role they play in such programmes. This is the case of the by FCPF supported East Kalimantan Jurisdictional REDD programme, which is the focus of this article. This programme was approved in 2019 by the World Bank and has run from 2019-2024. It covers the entire province of East Kalimantan, Indonesia. When this article mentions 'programme documentation', this is in reference to the East Kalimantan jurisdictional REDD programme (6).

The prominent role of NGOs represents a conflict of interest

According to the programme documentation, the Indonesian government initially intended to implement the FCPF's jurisdictional REDD programme in Indonesia in seven districts, located in four different provinces with widespread deforestation: Jambi, Central Sulawesi, Central and East Kalimantan. Two of these seven districts – Berau and West Kutai – are located in East Kalimantan.

Since 2008, TNC and WWF, have been involved with REDD-related activities in Berau and West Kutai. The programme documentation states that TNC and WWF have a “key role” as “implementation partners,” stating that these two organizations' experience offers “opportunities” for a bigger program in the future. The Berau Forest Carbon Program, set up by TNC, is referred to as “the first REDD+ program in Indonesia to span an entire political jurisdiction”, allowing it to “generate lessons for national REDD+ programs”.

The programme documentation also states that one important criterion to receive FCPF funding is the need for additional funding from other donors. While the other districts – which were part of the original proposal – were not successful in raising these extra funds, TNC ensured USD 50 million to go to Berau, while WWF and its partners ensured “up to US$ 82.5 million” in West Kutai (7).

There was no explanation as to why the decision was made to channel all the FCPF funding – USD 110 million - to East Kalimantan and not to the other provinces. But the strong impression remains that both TNC and WWF had a significant influence, revealing the conflicts of interest at play. For example, both NGOs prepared the ground with their activities in Berau and West Kutai; TNC was one of FCPF's founding members and donors and developed the idea of the FCPF together with the World Bank (8); and WWF participated in elaborating the programme documentation, which should have been the Indonesian government´s responsibility (9). There are additional examples of how these NGOs exercised their influence, which reveal the entrenched conflicts of interest (10).

In November 2022, the Indonesian government received the first advance payment of USD 20.9 million – equivalent to IDR 320 billion – from the World Bank (11). According to a letter from the Provincial government about the distribution of the money, “intermediary institutions” (NGOs, or lembaga perantara in Indonesian) will receive as much as IDR 3,190.914.000 in so-called Performance payments and IDR 19,502.000.000 in Reward payments. These payments amount to IDR 22,692.914.000, or USD 1.482 million – about 7% of the total initial payment of USD 20.9 million. One third of this money is for 'management fees', and two thirds are for 'program/activities' costs (12). If one takes into account the total approved amount of USD 110 million, based on this percentage, NGOs could receive up to USD 7.6 million of FCPF funding.

A programme full of contradictions

A programme focusing on those who do not drive deforestation

The programme documentation claims that the jurisdictional REDD Program in East Kalimantan is “designed to address drivers of deforestation”, and it identifies industrial oil palm plantations (51%), logging (22%) and mining (10%) as the three main drivers. However, as with TNC's pilot project in Berau, most of the Program budget- 53,2% - is focused on “providing alternative livelihood opportunities” to rural communities, including indigenous communities. This is in order to address “deforestation linked to encroachment and agriculture” [excluding oil palm], rather than on the main causes of deforestation: oil palm, logging and mining.

In spite of the programme's stated focus on “alternative livelihood opportunities”, this does not seem to be reflected in the reality on the ground. Three communities in West Kutai district, visited by WRM, JATAM Kaltim and NUGAL Institute in September 2024, complained through their local government representatives that the money they were promised for a project they presented to the programme coordination and which was approved, has not arrived yet. This is almost two years after the Indonesian government received its first payment from the World Bank. According to the villagers, each village was supposed to receive IDR 201,64 million, or about USD 12,938, mentioned too in the aforementioned letter from the provincial government (13).

Local government representatives have made several other complaints. One is related to how people from the REDD programme team came to the community to ask questions and fly a drone around, without explaining their objective or sharing the outcome of their survey. Local representatives have also questioned why each community in West Kutai is receiving the same amount of money, even though the smallest village in West Kutai has an area of 815 ha, whereas the biggest covers 56,957 hectares. This should translate into differential costs when it comes to forest monitoring. However, village size seems to be irrelevant to the programme coordination, which decided that all 82 villages included in the REDD program in West Kutai will receive the exact same amount. The community also complained that they have not been informed, nor consulted, about the REDD programme or about what REDD actually is. Only the community leader was invited for one information-sharing meeting, which took place outside the village territory.

One of the local representatives' complaints in particular stands out. Although the World Bank declares in the documentation that “communities will be able to select the benefits they prefer to access, which will reflect their priorities”, two villages had their community proposals rejected. Their proposal requested the purchase of car to patrol their forest area, which they determined to be a priority. The argument was that cars cannot be allowed because they contribute to global warming. This is quite a hypocritical reply, to put it mildly, for a programme that is built on the logic of generating carbon credits so that polluting industries responsible for the climate chaos can continue to destroy the climate. Meanwhile, the REDD programme penalizes communities that are not responsible for the climate crisis.

A programme ignores one of the main drivers of deforestation, mining

1,434 mining permits as of 2020 cover more than 5 million hectares, or 41% of the province’s territory (14). Mining companies, most of which are coal companies, are some of the biggest drivers of deforestation and other social and environmental violations in East Kalimantan. In the programme documentation, the World Bank expresses concern about the fact that the governor of East Kalimantan who took office in 2009 “campaigned on a platform of support to mining industries”.

However, “Mining companies are not included” in the REDD programme. They “will not implement any ER [Emission reductions] activities” with a footnote in the programme documentation, justifying the exclusion of mining on a governor's decision from 2018 that “suspends new coal mining permits, and adds additional requirements for companies who want to extend their permits”.

First, the argument that no new mining permissions will be given out is simply not true. For example, PT Adaro Energy, Indonesia's 2nd largest coal company, benefited from a new concession in 2024 (15). Besides, the governor´s decision from 2018 does little to prevent deforestation in the concessions that were given out before 2018, but are still under development. What's worse, ignoring the mining sector also underestimates the widespread phenomenon of illegal mining in East Kalimantan, which is causing even more destruction and risks than the legalized destruction.

Indonesia's mega-project of a new capital: a “manageable” kind of deforestation for the World Bank

Another major contradiction is exemplified in the construction of Indonesia's new capital city (IKN), a mega-project that was launched in 2020 in East Kalimantan. While on the one hand, the World Bank admits this “is likely to affect emissions in the province”, due to deforestation, it also states that the impacts of IKN “appear to be manageable”, arguing that it has the “potential” to “green” and “reforest” the area. The USD 30 billion IKN project has been particularly promoted by ex-president Jokowi, who wants to transform it into his main legacy.

What the World Bank considers to be “manageable” shows the complete ignorance of this multilateral institution, both about the scale of this mega-project (which increased in area from 180,000 to 256,000 hectares following its launch in 2020), as well as the social and environmental violations against the Balik indigenous people – whose territory overlaps with the capital construction site. Furthermore, there will be other, more devastating indirect impacts related to the construction of the new capital, which the World Bank is ignoring (16).

A programme that claims to have “results” even with deforestation on the rise

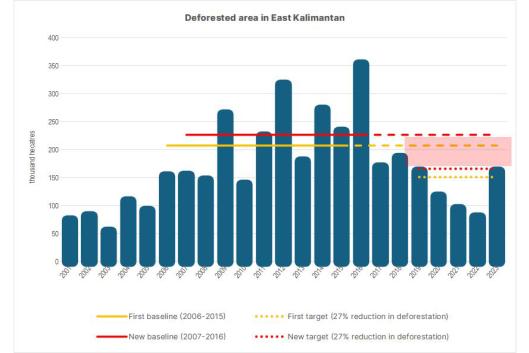

In order for jurisdictional REDD programmes to set a target for reduced deforestation, they first set a baseline; this involves defining a period of years over which the average annual rate of deforestation and forest degradation is calculated. In the case of the World Bank supported REDD programme in East Kalimantan, this period is 2007-2016. During this period, 700,800 hectares of forest cover was lost – or about 5.5% of the entire province. The next step is to set an emissions reduction target for the programme period (2019-2024), based on the average deforestation rate from the baseline period. In the case of the East Kalimantan REDD programme, the emissions reduction target set is 27%. This modus operandi raises at least two questions: What is the reasoning behind choosing one baseline period over another? And who makes these choices?

In the programme documentation, the first baseline period chosen was 2006-2015. However, in the final project document of 2019, this period was changed to 2007-2016. This seemingly small modification meant a significant change, because the new baseline period included the year 2016. This was a peak year in forest loss in Indonesia and East Kalimantan; massive forest fires hit Indonesia in 2015 but were only fully accounted for in the 2016 figures, due to a lack of image data of the 2015 destruction (see graph 1 below).

While the programme developers provided no justification for changing the baseline period, it is obvious that the new baseline makes it easier for the REDD programme to achieve “results”. Moreover, the deforestation rate in East Kalimantan reduced in the years after 2016, due to state policies as a reaction to the forest fires from 2015 that caused severe impacts. According to the REDD programme documentation, it was because of a national moratorium on primary forest clearance for plantations and logging.

Another consequence of the 'generous' baseline is that even though deforestation increased in the province, almost doubling from 79,200 hectares in 2022, to 161,000 hectares in 2023, the provincial government can still claim it has achieved “results”, as the graph above shows. This increased deforestation was due to the expansion of oil palm plantations, among other activities. (17)

Those who define the baseline and programme targets are the very same actors who are most interested in ensuring “results”, and therefore their own payments from the programme. These actors include the World Bank, the East Kalimantan government, TNC, and WWF.

Jurisdictional REDD also promotes carbon trading

Environmental and social organisations tend to critique private REDD projects much more than jurisdictional REDD programmes, also in Indonesia (18). One reason is probably due to the erroneous perception that carbon trading, the main critique of private REDD projects, is not involved in jurisdictional REDD programmes. Yet jurisdictional REDD programmes follow the same logic of focusing on carbon, carbon accounting and carbon trading – just like any other REDD project. And like other REDD projects, these programmes also use the same manipulation wherein project proponents themselves define baseline scenarios and 'results'.

In the case of the FCPF, most of the money has come from governments, such as Norway, Germany and the UK. But since this project's inception, there has also been money coming from private entities, such as TNC and the oil company, BP, which expect to receive carbon credits in return (19).

In recent years, carbon trading seems to play an ever-increasing role in the FCPF's functioning. Since 2018, the FCPF has engaged with CORSIA, the aviation sector's offsetting scheme. According to the World Bank, this scheme “is expected to offset more than 2 billion tons of CO2”. In 2023, the FCPF became eligible to supply CORSIA with carbon credits. By the end of 2023, the FCPF started to offer carbon credits for sale on the carbon market (20). In the latest update on the East Kalimantan FCPF programme on the World Bank's website, the programme is categorized as 'CORSIA eligible', meaning that East Kalimantan's REDD programme will allow the aviation industry to grow, whilst claiming it is not damaging the climate.

Final considerations

This article points to a number of contradictions in the jurisdictional REDD programme in East Kalimantan, based on the erroneous assumption that REDD is actually about reducing deforestation. REDD is not about stopping deforestation, but about creating more business opportunities for extractive industries and business-oriented conservationist NGOs, like TNC and WWF – all while increasing the threats to forests and forest-dependent communities.

Working under that assumption, what is written in most of the programme documentation makes much more sense. For example, the World Bank describes East Kalimantan as a province “rich in natural resources, such as timber, oil, gas, and productive soils”. Through such a lens, it makes perfect sense to exclude the mining sector from the scope of this programme, and to downplay the main drivers of deforestation, –logging and oil palm – by promoting certification schemes that have only helped expand these destructive monocultures. (21)

Understanding REDD as a policy that threatens forests also helps to better understand why there is a focus on the activities of people who are not a threat: forest-dependent communities. The World Bank describes them as “poor” in East Kalimantan – in contrast to the “rich” natural resources. The rural people, such as the Dayak communities, are particularly poor, states the World Bank. And the FCPF is creating new threats for their livelihoods. With NGOs like TNC and WWF involved as “implementing partners”, the focus is on creating more protected areas, without people. Never mind the fact that the World Bank and its business-friendly REDD programme does not hinder the threat of further mining, logging and oil palm expansion.

To provide a picture of what can really be expected from the REDD programme in East Kalimantan, let us quote once more from the programme documentation – this time from a rare passage of clarity amidst the blurred vision of the World Bank: “Expanding agriculture, logging, mineral extraction, urbanization and housing development have resulted in not only increased land conversion, but also forest degradation, reducing environmental benefits which further exacerbate poverty”.

NUGAL Institute, JATAM Kaltim and WRM International Secretariat

For security reasons, the names of the people who gave their testimonies for this article and the names of their communities are preserved

(1) See for example in https://www.ykan.or.id/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/ykan/laporan-kuartal-dan-tahunan-ykan/YKAN-Annual-Report_EN_.pdf, and also in https://www.undp.org/indonesia/press-releases/south-south-exchange-sse-2024-indonesia-leads-example-redd-knowledge-exchange

(2) News about ´fake credits´ and fraudulent practices are increasingly widespread. Additionally, projects imposed restrictions on the lives of forest-dependent communities that were already taking care of the forest.

(3) https://www.wrm.org.uy/15-years-of-redd-PIREDD-Plateaux-REDD-Project-DRC-Conflicts-Complaint-Mechanism

(4) https://reddmonitor.substack.com/p/world-bank-funded-zambezia-integration

(5) https://www.ykan.or.id/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/ykan/laporan-kuartal-dan-tahunan-ykan/YKAN-Annual-Report_EN_.pdf

(6) The programme documentation consists of a confusing set of documents that all have similar content, including the first 'readiness preparation proposal', presented to the FCPF in 2009, and approved in 2011; the first draft of Indonesia's jurisdictional REDD program presented in 2014 ; and the final proposal based on this initial draft that focuses on East Kalimantan: the East Kalimantan Jurisdictional Emission Reduction Program (EK-JERP), which was approved in 2019 and covered the entire province. The EK-JERP claims it will achieve 22 million tonnes of “verified CO2 emission reductions” from 2019-2024. In exchange, the World Bank has committed to paying an amount of up to USD 110 million, against a fixed price of USD 5 per tonne of CO2, based on a Benefit-Sharing Plan that was formulated by the Indonesian and East Kalimantan governments.

(7) TNC succeeded in raising funds from the governments of Germany (KfW/GIZ/FORCLIME), Australia, Norway, USA (a debt-for-nature swap scheme) and from charities like Ann Ray Charitable Trust and Grantham Foundation

(8) https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/history

(9) https://wwf.panda.org/es/?226019/Local-actions-lay-the-groundwork-for-REDD-implementation-in-Kutai-Barat-Indonesia

(10) For example, according to the Programme Documentation, the Regional Council on Climate Change (Dewan Daerah Perubahan Iklim), is a “key partner” in the implementation of the REDD programme, adding that it has “significant experience” in the “management of donor development funding”. This Council was created in 2011 and consists strictly of governmental representatives, however itcould count on “substantial support” from TNC (see here). Possibly one result of the ´substantial support´ that the Council opened the door for NGO participation in 2017 and, thus, increasing influence of NGOs in the programme. Another example is the signing of agreements and MOUs between NGOs and the provincial government, like WWF did in 2018 around the activity of measuring carbon, a key activity in any REDD programme. According to WWF, it is “the first online-based data cooperation model of calculating, monitoring, and reporting the carbon in Indonesia”

(11) https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/11/08/indonesia-receives-first-payment-for-reducing-emissions-in-east-kalimantan

(12) Provincial Government East Kalimantan, nr. 500-4/15008/EK from 10/10/2023 about ´Pembayaran Alokasi Insentif RBP FCPF-CF Untuk Kelompok Masyarakat´.

(13) Ibid

(14) https://news.mongabay.com/2020/01/indonesia-capital-relocation-borneo-kalimantan-tycoons-coal-mining-pulpwood/

(15) PT Pari Coal, owned by Adaro International Pte Ltd , PT Mitra Megah Indoprima, and PT Alam Tri Abadi. PT Pari Coal was granted a 24,971-hectare, 30-year concession by the national government on 01/02/2024. The location is partly on the border of Central and East Kalimantan, in North Barito and in Mahakam Ulu Regency. Adaro's coal will be transported on a special road that passes through Geleo Asa Village in West Kutai district; a port is being built too to facilitate the transport on the Mahakam River.

(16) This includes two hydropower dam projects: one is a 1,375MW plant that will directly affect the Mentarang and Tumbuh rivers; this project is already under construction and has already removed communities that are partly indigenous; the second one is a 9,000MW dam on the Kayan river, and construction has yet to start. If completed, both projects would further worsen climate chaos, due to the greenhouse gases that would be emitted from the forest being submerged. In addition to providing electricity for the new capital, the electricity generated would also fuel another devastating project in the region that is impacting other communities: the Green Industrial Park in North Kalimantan. Likewise, the coastal area of West and Central Sulawesi is being dismantled to dredge rocks that will be used as building materials for various IKN infrastructure projects. And what the Indonesian government promises to be a 'smart' city, means a city driven by electric transport. This fuels the demand for minerals like nickel, which has been causing severe social and environmental violations and protests in East Indonesia, for example on Halmahera island.

(17) Sawit Watch, an organisation that monitors industrial oil palm plantations and their expansion in Indonesia, has observed a trend of oil palm expansion in recent years. Furthermore, it disagrees with official figures of the area covered by industrial oil palm plantations in East Kalimantan – which the Ministry of Agriculture estimates to be 1,287 million hectares. Sawit Watch estimates the area of oil palm plantations in East Kalimantan to be 3 million hectares (Report and Projection, Indonesian Palm Plantation 2023, Sawit Watch)

(18) https://www.aman.or.id/filemanager/files/surat_terbuka_perdagangan_karbon_2023_231013_120638.pdf

(19) https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/donor-participants

(20) https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/sites/default/files/documents/_web_world_bank_2023_fcpf_annual_report_r01.pdf

(21) https://www.wrm.org.uy/other-information/sign-on-statement-rspo-failing-to-eliminate-violence-and-destruction-from-the-industrial-palm-oil-sector