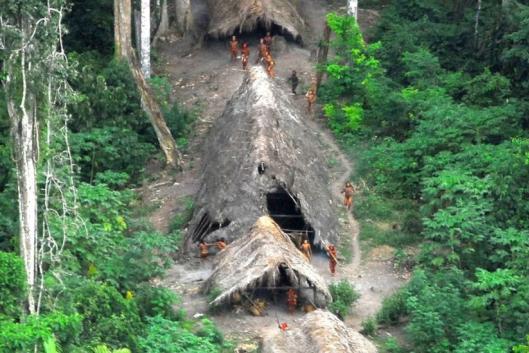

Several years ago, a photograph made headlines around the world. In it, an indigenous man in a small village in the middle of the rainforest is aiming a bow and arrow up at the airplane in which the photographer was flying over the scene. The photograph attracted international media coverage because it documented the existence of a group of indigenous people living in isolation in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest, removed from any contact with so-called “civilization”.

Photographs and news stories of this kind tend to frighten people. The media reinforce existing prejudices and stereotypes by reporting the “discovery” of “lost tribes” and highlighting the “threatening” gesture of the Indian aiming his bow and arrow at the photographer. These stories also tend to sensationalize the “primitive” way in which these people still live, something considered bizarre at the very least in a world where the majority of people have a cell phone, if not more than one, in which transnational telecommunications companies compete among themselves not only over “coverage areas” but also and primarily over people, viewed as “potential customers”.

At the same time, the photograph raises a question that remains hanging in the air: What is the significance of the fact that in the world today, in the 21st century, there is a group of people living in isolation, with little or no contact with the rest of the world? This is something that the media do not bother to investigate, or that they simply address in a very superficial way. This makes sense, because to explain it would be to admit that the “civilization” to which these isolated indigenous people do not belong and do not want to belong has historically been responsible for what can only be described as the genocide of indigenous peoples since the dawn of the colonial era. These uncontacted peoples demonstrate that “civilization” refuses to learn from its own mistakes and continues to seek out more land and “natural resources”. It continues to act in the same arrogant and domineering manner towards indigenous peoples, and particularly isolated indigenous peoples.

“Civilization”, which is often genuinely savage, based on an economic and productive system that exploits nature instead of protecting it and turns it into mere merchandise, is seeking to gain control over all areas that still remain free, in order to carry out more “development” projects. This includes the remote, difficult-to-reach areas of tropical rainforest where isolated peoples have sought refuge. What motivates these groups of people, of which there are currently an estimated 100 around the world, to live this way? According to researchers and support groups, these peoples simply want to live freely and independently, in accordance with their own traditions, beliefs and values – even if this means that many of them are forced to live constantly on the run because of the threats that surround them. They keep up their determined resistance against our society because of deeply negative experiences that they have suffered directly or indirectly in the past.

Perhaps their very existence is a perfect illustration of the crisis faced by our “civilization”. A society in which the majority live in overpopulated cities, where inequality and violence reign. A world in which the concept of “freedom” has become artificial, created in the imagination of “consumers” for the benefit of capital. One example is the promise of “freedom” through constant and “unlimited” access to telephone and internet service, dominated and controlled by transnationals.

At the same time, transnational corporations, with the support of governments, seek to perpetuate the gradual destruction of tropical rainforests, including those that are the “home” of isolated indigenous groups. Now they also want to gain control of intact forests in search of the new “gold”, namely “carbon credits” or “biodiversity credits”. Projects of this kind pose a real threat to isolated peoples, because they mean that instead of protecting their territories, governments will allow them to be accessed and controlled by the promoters of these projects, such as “green” corporations and big conservation NGOs.

It should be stressed that the rights and principles achieved internationally by indigenous peoples through their organizations and struggles do not address the specific situation of isolated indigenous peoples. For example, the internationally accepted principle of free, prior and informed consent is unworkable and inapplicable for these groups. How can they be consulted, how can they give or withhold their consent for “development” projects aimed at maintaining and reinforcing a “civilization” that they conceptually reject and want no contact with?

We believe that isolated indigenous peoples, with their stance of resistance and rejection towards the “civilized” world, have a great deal to teach us, without the need for us to isolate ourselves as they have. For example, these groups alert us to the need for deep reflection on how to confront the transnational corporations, banks and governments who continue to impose destructive “development” projects on us, who seduce communities with promises of benefits while history shows us that these projects offer nothing but destruction, not only of nature, but also of people, their values and their cultures.

It is urgent that we call on everyone to join in firmly defending the struggles of these isolated groups and peoples against the various threats to their survival. These peoples must have the basic conditions to guarantee their ability to survive as differentiated peoples, with the support of the state and society. It is crucial for isolated peoples to conserve their territories if they are to continue to live freely and offer hope to our crisis-stricken world. They can inspire us to seek out forms of struggle aimed at an alternative to this world of “development” and “civilization”.