“The stream is drying up. Over there, at that low-lying area, the eucalyptus is taking all the water; we aren’t managing to produce well.”

“Now three or four women have to fetch water together, otherwise it’s no longer possible [because of harassment by the company’s security guards].”

The above sentences and others below were said in August 2024 by community members of Nhamacoa, Nhamaduri and Cortina-de-ferro, in Gondola and Sussundenga districts, Manica province, Mozambique. Besides these, dozens of other testimonies were heard. They reveal the impacts suffered with the arrival of Portucel and its eucalyptus plantations in the region. These are reports of indignation in the face of empty promises of employment and improved infrastructure on the ground, as well as of conflicts with company representatives, guards and local authorities.

“In that patch of land Portucel cut down the trees and removed the stumps to plant eucalyptus [...] It was an area of forest and machambas [small plots for cultivating food crops].”

“The company promised [to build a] school, well, bridge, fix the road, and so far, nothing! All it did was give us a few kid goats and expired seeds.”

“The machamba I inherited is completely surrounded by eucalyptus; it is no longer productive because of the shade.”

The company has established not even 10% of the 240,000 hectares of plantations it intends to put in place as part of its eucalyptus “forestry” project. However, even this incipient presence has been enough to bring about various kinds of problems mentioned by the communities.

Who is Portucel?

Portucel Moçambique is a eucalyptus plantation company for producing cellulose, created in 2009 by Portuguese giant The Navigator Company, one of Europe’s largest paper and pulp corporations, and Portugal’s third largest exporter, accounting for 1% of the country’s GDP (1). In Mozambique, Portucel obtained from the government a concession to use 356,000 hectares for 50 years, renewable after that time, to set up the country’s largest pulp production project meant for export. It relies on planting extensive eucalyptus monoculture plantations in Zambézia and Manica provinces. The US$2.5 billion investment had a 20% stake from the World Bank, through the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

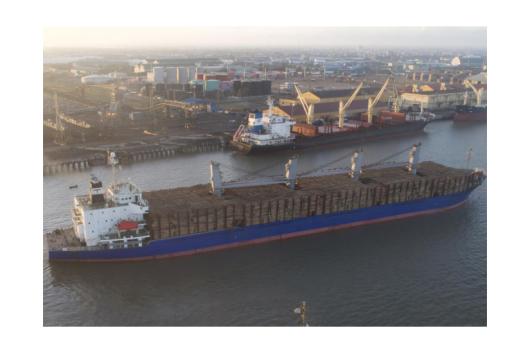

In October 2024, 10 years after planting began, the company’s plantations cover only 14,000 hectares, and the eucalyptus chip mill promised for 2023 never materialized. In 2020, the company started cutting to obtain its first crop, exporting raw timber. Since then, it has sent nine shiploads of eucalyptus trunks from the port of Beira to Portugal, totaling 285,000 cubic meters of wood (2).

After a period of delays and uncertainty, Portucel – Navigator’s largest investment outside of Portugal – renewed its promise to build a wood chip mill by 2026 and a pulp mill between 2032 and 2034. Hence, it is forecast that the company will expand its green deserts of eucalyptus over the next two years, reaching at least 40,000 hectares.

Portucel’s relations with communities

In its advertising, Portucel states it has already obtained 4,000 land cession agreements from families, stressing its “permanent dialogue” and alleged “monthly meetings with communities” (3). As for jobs, recently the company published a list of supposed positive returns from its plantations, with “qualified employment and professional mobility” appearing in first place (4). However, based on numerous accounts heard on several visits we made to communities affected by Portucel in the two provinces in question, we can state that the company’s publicity is absurdly fantastical. The lack of transparency of the pitiful community consultations, the small number of job offerings and the precarious working conditions have been recorded many times by means of visits, accounts and scientific publications (5). All this evidence was once again corroborated by the testimonies recently heard in Manica province.

Obscene accumulation

However, one of the statements made by Portucel in its advertising cannot be denied: that its activity means “wealth and added value generation in the country”. Doubtless, the acquisition of cheap lands in the Global South by corporations from the Global North, with the support of international agencies, associated with the employment of highly exploited cheap labor, represents gigantic possibilities for generating wealth IN the country. It does not mean, however, that the wealth REMAINS in the country, and even less with the PEOPLE of that country.

The case of Portucel/Navigator, the self-proclaimed “world’s most sustainable forestry company” (6), is an example of how the propaganda of sustainability and of social benefits legitimizes a process of primitive accumulation (appropriation of extensive tracts of land) that allows a corporation from the Global North to transform people and nature into mere resources of production (labor and land) and insert them – at a very low cost – in the circuit of expanded reproduction of its capital.

Although communities denounce countless irregularities and violations by Portucel/Navigator, the very rules of the game endorse the injustice that the business represents. For example, in 2022, Navigator distributed 200 million euros in dividends to its (few) owners. Of this, 70% went to the Semapa conglomerate, which belongs almost totally (83%) to Sodim, the holding company of the Queiroz Pereira family (7). A group of 45 dwellers from the communities with whom we spoke was shocked to learn that it would take more than 2300 years (!) of non-stop work – assuming they got paid the agreed daily rate, which is not always the case – to collectively earn the same amount received in one year by the heirs of a single family, only taking into account what they earn in terms of profits due to their ownership of a company’s shares, that is, without necessarily having worked (8). This comparison exposes absurd and obscene inequality levels, naturalized by a development model that basically promotes land grabbing and, in Mozambique, is materialized in the expanding eucalyptus monoculture plantations of Manica and Zambézia provinces.

“The company got here saying ‘whoever hands over the land will get a job’.”

“Work lasts 15 or 30 days then it ends. And they deduct everything they can from the pay.”

“Payment is always late and disorganized.”

“They gave us company caps and T-shirts just to take photos.”

Resistance

Faced with the injustice that the corporation does its best to cover up or ‘wash’, part of those affected, in conjunction with community associations and partner organizations, insist in resisting the green deserts of tree plantations.

With this aim in mind, a gathering was held in August 2024 in Manica province. It brought together 50 members of communities affected by tree plantations and was organized by Justiça Ambiental, the World Rainforest Movement, Missão Tabita and the Montes Errego Young Combatants’ Association. Communities were visited and several reports of violations were heard, including of the right to community consultation, labor rights and the right to physical integrity, as well as accounts of environmental impacts that affect food production by communities that surround plantations. While some still believe the companies will fulfill their promises – build schools, build bridges, “give” jobs –, others feel indignation, and the will to no longer allow the planting of new areas and to take back areas unduly appropriated by the company.

Based on the gathering, on the International Day of Struggle Against Monoculture Tree Plantations (September 21), Justiça Ambiental published a statement celebrating resistance to the plans of forestry corporations and urging the Government of Mozambique to invest in diversified food production based on agro-ecology, as well as to promote and facilitate community-based income generation initiatives (9).

Hopefully the Mozambican people and communities will make use of their constitutional right to resist whenever they need, so that the sovereignty of those who live from the land will prevail over those who only want to profit from it!

WRM International Secretariat

(1) As indicated by Agroportal in May 2024. See here.

(2) As indicated by material made public by Portucel in October 2024, available here.

(3) Ditto.

(4) Ditto.

(5) For more details, check publications by Justiça Ambiental here and here, WRM and Observatório do Meio Rural de Moçambique.

(6) According to a press release from Navigator in July 2024, available here.

(7) Data regarding the distribution of dividends obtained from the corporation’s website; data regarding the corporation’s shareholder makeup available at the corporation’s accounts’ report; and information referent to Sodim obtained from Jornal de Negocios.

(8) Considering the daily remuneration of 3 euros (about 210 meticais) paid by Portucel per manual worker, it would require a group of 45 workers selling their labor every day for 2358 years to accumulate 116.2 million euros, i.e., the amount paid in dividends by The Navigator Company to Sodim, holding company owned by the Queiroz Pereira family, in 2022, if one considers the abovementioned percentages of share ownership.

(9) Read the full statement here.