The Orinoquía refers to the territories encompassed by the immense Orinoco River Basin in Colombia and Venezuela. This area is comprised mostly of flat lands, which is why it is known as the plains region. It is one of the largest savannahs on the planet, along with the African savannah and the Brazilian Cerrado. In Colombia, the Orinoquía is mostly located in the departments of Arauca, Casanare, Meta and Vichada, covering some 310,000 Km2. (1)

This vast area is home to Indigenous Peoples, peasants, settlers, Afro-descendants and an urban population. The latter has grown significantly in recent decades, in cities such as Villavicencio, the capital of Meta. Part of this urban growth is due to the arrival of people from the rest of the plains who have been displaced by the armed conflict that still affects the country.

The Orinoquía has undergone drastic territorial transformations since the time of the European occupation, when extensive cattle ranching was introduced. Then came extractivism, with the largest volume of oil in Colombia being exploited in this region. At the beginning of the 1960s, the State pushed thousands of families into the region through targeted colonization programs; many of the properties originally given to the families through these programmes later ended up in the hands of landowners; this led to the families being displaced once again.

By the 1980s, crops grown for illicit purposes (mainly coca) occupied vast areas, and the armed conflict intensified. The Orinoquía was one of the most affected regions (2). Subsequently, a new, "licit" economic activity was introduced, which transformed and impacted the territory and its inhabitants again: large-scale tree plantations.

Tree plantations for the carbon market

Tree plantations or monocultures have a variety of characteristics. This article seeks to delve into, and warn about, the characteristics and impacts of one specific kind: plantations earmarked for the carbon market.

This is nothing new. During the first decade of this century, these monocultures began to be implemented and promoted as carbon sinks. In the last three years, the number of applications to establish and register tree plantations as carbon projects has noticeably increased, both in terms of the number and the size of projects (3).

But where does the interest in these plantations come from? Basically, it comes from the opportunity – for logging and pulp companies – to do more business and make more money. Many companies that purchase “carbon credits,” or pollution credits, are also interested in greenwashing their image (4). They are taking advantage of the postulate that trees absorb carbon from the atmosphere and store it in their leaves, trunks and roots. So, those who install plantations and claim that they are only doing so for the carbon market can make money by selling carbon credits to companies that claim they cannot reduce their own pollution (5). However, it is usually not true that project developers only install plantations for the carbon market; they likely are going to install the plantations anyway, in order to continue selling timber and making money.

The carbon market and carbon projects have not done a good job of achieving their promise – that is, to solve the climate crisis. But they have worked out very well for companies that take advantage of this business by offering their services: in consulting, certification, creation of carbon standards, carbon credit trading, etc. Additionally, this market benefits the very companies that are the main culprits of the climate crisis. Rather than cutting or decreasing their emissions, these companies are maintaining or increasing them, whilst growing their profits.

A Friends of the Earth publication provides an extensive list of the misguided actions of, and impacts caused by, plantation projects related to carbon offsetting (6). These include:

• violating the laws in different countries regarding communities' access to land and their right to free, prior, informed consent;

• evicting farming families from their land;

• buying land at very low prices or conducting violent land grabs;

• in the case of projects where farmers sign contracts to plant the trees, obligations that exceed the time frame stipulated in the contracts – for example, to provide maintenance on trees for 50 or 100 years, when a contract only lasts seven years;

• negatively impacting food security and food sovereignty, since families must abandon their crops in order to focus on project activities;

• and causing accidental fires, in the case of some companies.

These facts give communities ample reason to be alarmed and concerned, especially in the Global South, where these kinds of plantations are growing the most. Of particular concern is what may happen in Colombia, which is one of the three countries with the highest number of tree plantation projects for the carbon market.

Plantations for the carbon market in Orinoquía

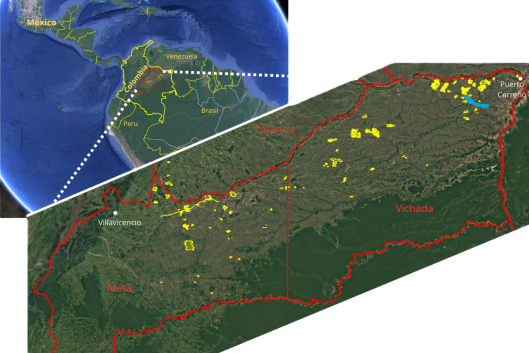

The Orinoquía has the largest area of tree plantations earmarked for the carbon market in Colombia. There are at least 28 projects covering approximately 178,000 hectares (7). This number is higher if we include projects that have not been registered yet. While other parts of the country have a greater number of projects, such as the department of Antioquia, those plantations cover a much smaller area.

Because the Orinoquía, and in particular the departments of Meta and Vichada, has the largest area of plantations in Colombia, this is also the region with the greatest number of risks and impacts.

Furthermore, the track record of existing plantations in the region is alarming. The Orinoquía is one of the regions that has been severely impacted by the armed conflict in Colombia. Thousands and thousands of people have been killed, displaced, disappeared or violated in the most atrocious ways in this conflict. Some of the suffering and impacts caused by this conflict are directly related to the installation of plantations. In turn, plantations are one of the causes of the transformation of the territory and landscape.

But why are plantations in Orinoquía so harmful?

Many of the projects that are planned or underway propose to restore and recover territories, which they call ecosystems, through reforestation or afforestation. This is where inconsistencies and objections become evident – first of all, because the reference to 'ecosystems' omits any reference to the territory. The territory is what is really being impacted, and this includes not only the elements of an 'ecosystem' – primarily water, soil, vegetation and animals – but also human populations, relationships and cultures, among other elements.

Secondly, these projects claim, a priori, that they will restore lands degraded by extensive cattle ranching or agriculture. To this end, they promise to establish 'planted forests' on degraded savannahs – though the characterization of 'degraded' can be debated or contested. Most of these savannahs are located south of the Meta River, on the high plains. These savannahs are part of the territorial diversity of Planet Earth, and not all of them are covered with trees. The presence of soils covered by grasses does not mean that the lands are degraded.

"It is clear that the savannahs of the high plains have not been deforested recently. On the contrary, the savannahs of the Orinoquía have been predominantly grasslands for the last 18,000 years, or more," explains Sergio Estrada (8). Afforesting or reforesting the savannahs has multiple consequences, especially considering that most of these projects consist of monocultures of exotic species, such as pine, eucalyptus or acacia trees (9).

Ecological impacts of monoculture tree plantations on the high plains

At the end of the day, plantations are not forests. And these projects, whether focused on reforestation or afforestation, are leading to a loss in biodiversity – since native species are losing their habitats or being replaced by introduced species. When the savannah is transformed, large mammals like the anteater – which depends on termites and ants – flee in search of other places to feed. Multiple and unimaginable alterations to the habitat occur; for example, exotic tree species do not produce fleshy fruits that are able to feed the local fauna. Only some parrots consume the acacia fruits (Acacia mangium), which causes another imbalance, as it helps propagate this highly invasive tree far from where it was planted (10).

Meanwhile, several projects claim that they are recovering degraded lands, yet they have installed plantations in areas that are well-known for their good state of protection. Such is the case of the Bita river basin, which still has almost 95% of its natural cover (11). Some of the plantations of the Green Compass project, owned by the Trafigura corporation (one of the world's largest fossil fuel traders), are located in the vicinity of this basin. The company has invested more than $1 billion through one of its subsidiaries, Impala, to adapt infrastructure to transport oil along the Magdalena River in Colombia (12).

The Green Compass project, most of whose plantations are in the area highlighted in blue in Figure 1, is managed by Inverbosques. By 2024, Inverbosques had 10,000 hectares planted in Vichada, 90% of which were eucalyptus trees. The company's manager defends the decision to plant eucalyptus for economic reasons. She claims that this species allows for an accelerated capture of carbon credits to finance the project and "eventually" plant native species, which grow very slowly and are harder to produce efficiently in economic and financial terms (13).

A significant number of these plantations are being established, or will be established, on the most fertile soils of the high plains: the banks of the Meta river. This means that they receive water coming from the eastern mountain range that has a high nutrient content.

So, the proposal is to transform well-protected territories into monoculture tree plantations. But what is even more alarming than the effects described above are the impacts on communities and Indigenous Peoples.

Violence and dispossession caused by the installation of plantations in the Orinoquía

The Orinoquía already has a vast expanse of monoculture plantations, not only of trees, but also of oil palm, maize, soy and sugar cane, among other crops. There are also existing carbon plantations, such as the Gaviotas 2 project, which aims to plant 6.3 million hectares earmarked for agrofuels and to serve as carbon sinks (14).

Multiple sources have documented the systematic practice of dispossession and displacement of indigenous communities and peoples, whose territories are frequently used to establish plantations; this is especially true so far for the 21st century. The Colombian State has been involved and bears responsibility in different ways – whether through neglect, by promoting impunity, or through systematic practices, such as not responding to indigenous people's requests for territorial recognition. In some cases, the State has ignored the existence of these groups. Meanwhile, settlers and private individuals have been given titles to the territory, which they later sell to companies that install palm, timber species, or other kinds of monocultures (15).

Indigenous Peoples of the region have been decimated by practices that include even hunting them – through what are known as Guahibiadas. There are reports of this occurring through 2005 on the outskirts of Puerto Gaitán (Meta) and Vichada (16). Thus, any intervention that displaces Indigenous Peoples or endangers their territory has a severe impact on their survival.

In the department of Vichada alone, the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC, by its Spanish acronym) and the Regional Indigenous Council of Vichada (CRIVI, by its Spanish acronym) identified 41 cases of communities at high risk of displacement and territorial expropriation in 2009. The ethnic groups affected were the Sikuani, Mayerri, Kuiva, Amorúa, Sáliva and Piapoco Peoples. At that time, seven cases involved violent displacement, including the burning of villages or the intention to do so in order to set up rubber or agrofuel plantations. Two companies are linked to these events: Hercaucho and Llano Caucho (17).

In short, the presence of plantations in the Orinoquía has been tied to practices of dispossession, violence and displacement, which lead to the loss of Indigenous Peoples' territories.

With the incentive of carbon markets, the establishment of new plantations tends to exacerbate the very serious situation of rights violations for local peoples and communities. The demand for land will also increase, leading to more conflicts. It is important to raise awareness about this situation, so that measures can be taken to avoid repeating patterns that have already been identified when plantations are established in the region.

All of this is occurring in a context in which both local populations and Indigenous Peoples have almost no knowledge of this new carbon business and its implications; therefore their capacity to organize and respond is low.

Meanwhile, plantations for the carbon market are growing in the Orinoquía, under the absurd claim of restoration. But the opposite is true: these plantations are causing a number of impacts on the region and its inhabitants. Therefore, they represent a continuation of an unjust system of land grabbing, perpetuated by violence and exploitation.

(1) National University of Colombia - ODDR. 2013. Characterisation of the Orinoquía region. Bogotá D.C.

(2) The final report of the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-repetition. This report was created in the framework of the peace agreement between the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – FARC-EP (People's Army); in its chapter on Orinoquía, it provides details on the situation of violence and rights violations in that region

(3) This WRM publication from 2024 shows where and how these kinds of plantations are expanding, who they benefit, and how they are impacting communities: "Tree Plantations for the Carbon Market. Why, how, and where are they expanding?". Available here

(4) For more information about what carbon credits are and who benefits from trading them, see the article "The carbon business, land and trees"

(5) This WRM publication from 2024 shows where and how these kinds of plantations are expanding, who they benefit, and how they are impacting communities: "Tree Plantations for the Carbon Market. Why, how, and where are they expanding?". Available here

(6) Friends of the Earth International. 2023. Bank of evidence on false climate solutions: Their impacts on peoples and the planet. Available here

(7) Data obtained in January 2025 from the certification companies, Verra Verified Carbon Standard, Cercarbono, Biocarbon and Gold Standard.

(8) Estrada, V. S. 2024. Evitemos una tragedia ecológica en las sabanas del Vichada. Revista Nova et Vetera. Volume 10, Number 92.

(9) To learn more information about the problems caused by industrial tree plantations, we recommend the publication "What could be wrong about planting trees? The new push for more industrial tree plantations in the Global South". Available here

(10) Estrada, V. S. 2024. Evitemos una tragedia ecológica en las sabanas del Vichada. Revista Nova et Vetera. Volume 10, Number 92.

(11) Mongabay. 2018. El río Bita se convierte en el undécimo humedal Ramsar de Colombia. Available at here.

(12) Mongabay. 2024. Experts question benefits of Colombian forestation project led by top oil trader. Available here

(13) Idem.

(14) Bohórquez, D. A; Garcés, A.D; Ayala, R. S. 2012. Análisis de conflictos de la región Orinoquía en relación con proyectos energéticos: 2000-2010. Research in progress, Number 27, pp 87-152.

(15) ONIC. 2009. Introduction to the situation of human rights violations in Vichada.

(16) Truth Commission. “Afectaciones históricas, continuum de violencias: Guahibiadas”. Available here.

(17) ONIC. 2009. Territorial situation of indigenous peoples in Vichada.