The Orinoquía region is one of five geographic regions of Colombia, spanning the departments of Arauca, Casanare, Meta, Vichada, and the northern part of Guaviare. Also known as Los Llanos, this region contains great cultural and ecosystemic diversity, including foothills, transitional forests, savannahs, floodplains, mighty rivers, and a large variety of flora and fauna—some of which is in danger of extinction.

The Orinoquía region has been described as “empty;” its common name, “plains,” refers to a flat, uninhabited and wild area (1). Yet, this region is home to a diaspora of nomadic Indigenous Peoples who have ancestrally inhabited the area. Today, these peoples are either confined to established indigenous reserves, or they live in settlements that State authorities, such as the Ministry of Interior, have not yet recognized (2). The Constitutional Court has declared that most of these populations are at risk of physical and cultural extinction (Order 004) (3). Due to the structural racism and ethnocide they have suffered, these populations currently do not have the physical or cultural means to survive (4).

The Colombian state continues to promote the idea that this territory is “empty” and available to be used as an agricultural reserve. To this end, it has given usufructuary land titles to large national and foreign capital interests, without taking into account the existence of communities, nor their right to participate in decisions that affect their lives. The state has not applied a necessary differentiated approach when considering activities and projects that directly affect indigenous territories and territorialities (5).

The ancestral culture of the peoples of the Orinoquía contrasts with the violent development strategy that is currently being implemented in the territory—via targeted colonization programs, and exploitation of rubber, cinchona, indigo, hydrocarbons, monocultures, and cattle ranching (6). Additionally, the region has recently been designated as “a great agricultural pantry” on which to expand agribusinesses, carbon capture and offset projects, and rare earth mining.

With the approval of document 3797 of the Economic and Social Policy National Council in 2014 (CONPES, by its Spanish acronym), the Colombian state determined that a portion of the Orinoquía, called the high plains, would be an agricultural expansion zone—highlighting its potential for large- scale oil palm and mining projects (7). This document made no mention of Indigenous Peoples, their productive projects or their organizational processes.

Let's look at three recent examples of external intervention in the territory.

Vichada and mining: The Orinoco mining arc

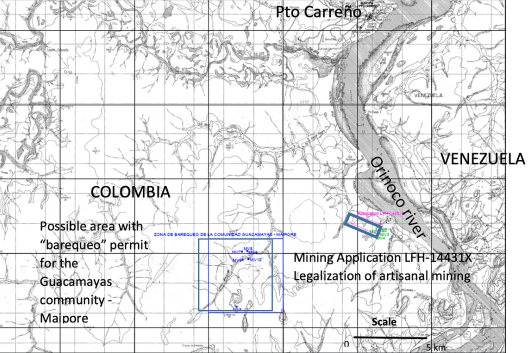

Mineral reserves in the Colombian Orinoquía region have a high value on the international market, due to the presence of rare earth minerals (8). In 2012, the Colombian State demarcated areas in the department of Vichada as Strategic Mining Areas (AEM, by its Spanish acronym) through resolution 0045 of the National Mining Agency (ANM, by its Spanish acronym) (9). However, this resolution—along with others of a similar nature—was declared to be null and void by the Constitutional Court in 2015, due to violations of the rights to prior consultation, cultural diversity, citizen participation and territory (10). Prior to that Court decision, though, 190 applications for mining titles had already been filed with the authorities (from 2003 to 2012). The total area of these titles amounted to 895,908 hectares, or the equivalent of 9% of the department (11).

In 2022, the indigenous community of the Guacamayas Maipore Indigenous Reserve in Vichada began to express concern about mining activities in their reserve and in a neighboring area. Auxico Resources, a Canadian multinational mining company, had negotiated to acquire a property adjacent to the Indigenous Reserve—which since 2010 had been under a process of approval for artisanal mining. But in 2023, the National Mining Agency granted the mining title to Auxico Resources, and in 2024, the environmental authority (Corporinoquía) approved the Environmental Impact Study for this project (12).

Auxico Resources claims to have a memorandum of understanding with the Guacamayas Maipore Reserve to mine within this territory (13). Yet the majority of the Reserve's inhabitants deny this, saying that only one person signed the documents without the participation of the community. Now the inhabitants fear that the company will begin exploiting the metals in the Reserve without their consent within a few years. Meanwhile, the environmental impact studies have not taken into account the effects on surrounding communities, and there are no preventative measures or environmental offset activities planned.

Auxico Resources uses the term “artisanal mining” strategically to gain the rights to exploit under less stringent standards. One might wonder what kind of “artisanal” mining a multinational company would do, when it has strategic interests beyond our borders and plans to build a rare earth refinery in Colombian territory. It is also unclear who would be responsible for the obligations that this license entails: would it be the company, or the person from whom they purchased the land? Who would be responsible for any environmental or social impacts caused by the company (14)?

Casanare: Caño Mochuelo and the conflicts surrounding two “environmental” projects

The Caño Mochuelo Indigenous Reserve, located in the department of Casanare, won an important victory in 2010: in a general assembly, the communities decided to prevent oil exploration in their territory (15). However, the communities are now debating about two projects that are part of the “green economy”—a trend that Iván Duque's government originally promoted, and Gustavo Petro's government later expanded upon. These two projects are 1) the sale of carbon credits, and 2) a 200-hectare “reforestation” project with eucalyptus species.

The Caño Mochuelo Reserve is a rather unique case in Colombia's cultural pluriversity. In an area of less than 100,000 hectares, ten different Indigenous Peoples are confined within 14 settlements; these Peoples have nomadic or semi-nomadic traditions and have historically been physically and culturally exterminated (16). As a form of governance and participation, the communities have a General Assembly. Yet sometimes the decision of the Assembly is not respected, and one person ends up making a decision for all 14 communities.

Carbon credit project (2022)

The communities living in the Caño Mochuelo Reserve are impoverished due to the lack of attention and educational and employment opportunities. They are also victims of multiple violations of their human dignity, which the Colombian State itself has recognized in its process of collective reparations for victims of the armed conflict (17).

Since 2022, the CO2CERO company—through a private individual, Henry Andueza Errunuma—has been promoting a project to sell carbon credits, which would be implemented in the Reserve. The agreement would be signed between the company and Andueza, who would act as a REDD+ coordinating partner on behalf of nine Indigenous Reserves. Yet the agreement does not specify the kind of activity through which the carbon credits would be generated (e.g. conservation, tree plantations, etc). On the company's website, there is a project registered under the name of Awia Tuparro +9, in which several indigenous territories are mentioned; however the Caño Mochuelo Reserve does not appear on this list (Proyectos de Carbono – CO2CERO).

In their social outreach for this project, project proponents have not employed the protocol of free, prior and informed consultation. Believing that the commercial nature of the contract makes them exempt from certain protocols, proponents claim that it is a free-will agreement among the parties. Despite the existence of tools like the social, environmental and institutional safeguards enacted in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, there is no guarantor, in practice, to enforce communities' minimum rights to citizen participation and access to information (18).

This contract has some particularities that are worth mentioning:

• The contract is a power of attorney (mandate contract) in which the Reserve grants a third party the ability to negotiate on its behalf.

• The contract has confidentiality clauses that undermine the social safeguards on access to information.

• The contract stipulates that the Reserve must be responsible for guaranteeing social and environmental safeguards, despite the companies' real obligations in this regard.

• Despite the claim that these investments are a part of communities' so-called “life plans,” the communities of the Reserve currently do not have such plans. A “life plan” is a tool that communities develop in order to be able to inhabit their territory with their own culture and identity. A “life plan” covers several areas, including spiritual, political, environmental and economic.

• The non-compliance clauses to which communities would be liable amount to $100,000,000 Colombian pesos (USD 25,000).

• Once the studies have been carried out, if the project is considered to be infeasible, the costs must be assumed by the Indigenous Reserve.

The carbon credits project was not approved through the normal channels of the Reserve's General Assembly, but rather through an entity that does not exist in its statutes: a board of directors made up of 14 authorities. This board did not take into the account the will of the communities, which had already repeatedly expressed their objections to the project in assemblies.

Yet despite the fact that the General Assembly decided not to move forward with the project (in April 2024), the Governor of the Reserve had already signed the contract for the project in December 2023, without the Assembly's authorization. This makes it challenging to stop the project without legal ramifications.

Eucalyptus “reforestation” project (2024)

In December 2023, the former governor of the department of Casanare, Salomón Andrés Sanabria, and the current governor of the Caño Mochuelo Reserve, surreptitiously agreed to reallocate money from the General Royalties System. These funds, which had been designated for educational infrastructure in indigenous schools, were reallocated to “implement actions to improve the quality of life of the indigenous community of the Caño Mochuelo Indigenous Reserve, through productive reforestation in the municipality of Paz de Ariporo” in the amount of $7,000,000,000 Colombian pesos (USD 1,700,000) (BPIN Code 2023100010060).

There was no prior consultation about this project, and the Assembly did not approve it. There was only a private document signed by the governor of the Reserve. Meanwhile, the Caño Mochuelo Reserve had already established that the royalties from the State were to be used for educational infrastructure in indigenous schools in Casanare—as previously stated in both internal documents and agreements with other indigenous groups in the department of Casanare (19). Why, then, was the communities' decision modified?

This project aims to plant 200 hectares of eucalyptus trees in the middle of the Casanare savanna. The argument is that planting these trees is an efficient way to “rebuild” and “recover indigenous identity.” However, the negative impacts of eucalyptus monocultures are well documented. One of these impacts is the high consumption of water, including of water from the water table.

More examples of carbon colonialism and racism in Orinoquía

Long before the project in Paz de Ariporo, foreign investors from the company, Forest First Colombia, appropriated 40,000 hectares in Vichada to install a eucalyptus plantation. The aim of the plantation was to make money from the sale of carbon credits. In an interview, company representatives claimed that “in this area of Colombia, not only are there no carbon stocks in the soil, but there is also no vegetation to hold that carbon.” They added that eucalyptus, in contrast, was “very efficient at taking carbon out of the air and storing it in the wood.” Echoing the Colombian government's characterization of the region as ‘empty,’ project representatives claimed that they were “not displacing people.” Meanwhile, they accuse the grassroots communities of environmental destruction, while turning a blind eye to how their own eucalyptus monocultures cause destruction: “the few people who live there set the grassland on fire multiple times a year due to poor land management practices” (20).

Ironically, the environmental impact study for the Paz de Ariporo project justifies reforestation with eucalyptus trees using the argument that it will help recover the cultural identity of the indigenous communities—when in reality there is no cultural relationship between these trees of Australian origin and the communities of the Orinoquía region.

It is worth mentioning that if the goal of the project were focused on strengthening Indigenous Peoples—and not just capital interests and the contractor friends of the current government—the reforestation project would have been planned using multiple species of the Arecaceae (palm) family. Due to the high demand for palm trees, and the very reduced space that the communities have, these trees have disappeared from the Reserve.

Arecaceae trees are not only the most important source of raw materials for construction, and for the manufacture of tools, clothes, crafts, medicines and food, etc; they are also part of a theological universe that interweaves all organisms that coexist in the Orinoquía region. The moriche palm (Mauritia flexuosa) stands out due to its complex relationships of association with multiple species; this is why it has been named a keystone species for life. A similar phenomenon occurs with the seje palm (Oenocarpus bacaba), the royal palm or cucurita (Attalea maripa), the cumare palm (Astrocaryum aculeatum) and the Açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea) (21). The communities of the Reserve believe that the wisdom of their ancestors is embodied in these species of palm trees and other plants of the Reserve.

Despite these facts, government institutions are not taking responsibility for the environmental impacts caused by this project, nor are they guaranteeing the collective rights of the communities or adequate consultation. This leaves the communities in a vulnerable situation.

Corporación Claretiana NPB (22)

Andrés Tiboche and Daniel Ávila

(1) Rausch, J. M. (1999). La frontera de los Llanos en la historia de Colombia : (1830- 1930) / Jane Rausch ; translation Nicolas Suescún. Santafé de Bogotá: Banco de la República, El Ancora

(2) The Indigenous Reserve is a political-administrative entity, taken from the colonial era, that seeks to protect the territory of indigenous communities, with respect for their autonomy and self-determination, in accordance with ILO Convention 169.

(3) https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/autos/2009/a004-09.htm

(4) As evidenced in the report that the Llano & Selva Network presented to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP, by its Spanish acronym), “Ethnocide and Structural Racism in the Orinoquía,” in 2021.

(5) The Constitutional Court has recognized indigenous communities' “territorialities” as places that, though not within their officially demarcated territory, are part of their culture due to spiritual and cultural relationships. SU 123 from 2008.

(6) Editores. Gómez G., A. (1991). Indios, colonos y conflictos : una historia regional de los Llanos Orientales, 1870-1970 / Augusto Gómez G. Bogotá: Siglo XXI Editores, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

(7) National Council for Social and Economic Policy, a body responsible for advising on the country's economic and social policies.

(8) Rare earth minerals are a special group of minerals that have a high commercial value for technological development.

(9) DIARIO OFICIAL. AÑO CXLVIII. No. 48483. 6, July, 2012. p. 131. In: https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?id=4007264

(10) Ruling from Tutela T 766 from 2015 https://justiciaambientalcolombia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/sentencia-t-766-2015-1.pdf

(11) Rojas, I., Ospina, J. & González O. (2019) Vichada: Tierra Codiciada. In: TERRITORIO Y DESARROLLO 2019; January-June. Vol. 3, N°1. PP. 13-19.

(12) https://www.elespectador.com/investigacion/la-historia-no-contada-de-la-primera-mina-de-tierras-raras-en-vichada-colombia/#google_vignette

(13) https://www.auxicoresources.com/_files/ugd/6f9bc0_4801a8ed522945498617f1d95afbfc12.pdf

(14) The Colombian government is currently working with indigenous communities to update the mining code; however, we have been able to demonstrate that the issue of rare earths has not been directly addressed, and there is a significant lack of knowledge about this kind of project.

(15) https://sistematizacioncm.wordpress.com/4-el-proceso-de-intervencion/el-proceso-de-intervencion/2010-2/ Article 1 of Resolution 0171 from 2016 of the Unit for Comprehensive Attention and Reparations to Victims defines confinement as a situation in violation of basic rights, in which communities—despite remaining in a part of their territory—lose mobility, due to the presence and actions of illegal armed groups. This restriction means they are unable to access goods that are indispensable for their survival, because of the military, economic, political, cultural and social control exerted by illegal armed groups in the context of the internal armed conflict.

(16) In the framework of the Colombian State's process on collective reparations for the victims of the armed conflict, there is something called a precautionary measure: a preventative legal contract to avoid causing greater damages than those already caused. This has been established via Order 098.

(17) As this article was being written, the Colombian Constitutional Court recognized these violations of communities' collective rights in its ruling T 248 from 2024, as well as the Colombian State's failure to apply an ethnic approach in the voluntary REDD+ market.

(18) The General Royalties System (SGR, by its Spanish acronym) is a mechanism that seeks to guarantee the equitable distribution and efficient use of revenues from exploitation of the country's non-renewable natural resources.

(19) https://dfcgov.medium.com/a-q-a-with-forest-first-colombia-ceo-tobey-russ-and-cfo-jonathan-dodd-on-climate-change-mitigation-06e33921cd4d

(20) Schultes, R. E. (1974). Palms and religion in the northwest amazon / Richard Evans Schultes. Cambridge: Harvard University.

(21) Organization that has been accompanying indigenous communities of the Orinoquía region for over 20 years.