(Disponible uniquement en anglais)

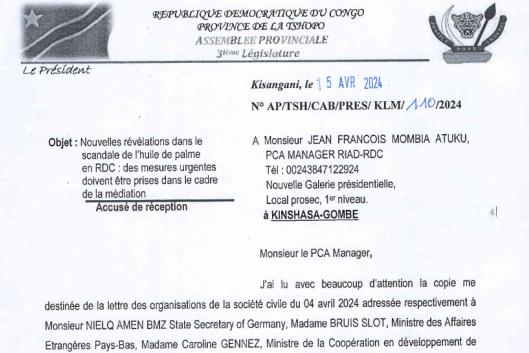

On April 15, Mateus Kanga Londimo, the president of the legislative assembly, sent a letter to RIAO-RDC, a civil organization in DRC to express his support for a call by international NGOs to pause a mediation process between the oil palm company PHC and communities affected by its land grabbing. The largest portion of the PHC concessions are located in Tshopo province. In his letter, the assembly president said he agrees with the demand of “pausing the mediation in order to find out how to support the communities on a legal level”.

Documents released as part of a court battle between current investors of PHC in the US revealed that European development banks thwarted the return of nearly 60,000 hectares of land grabbed from the communities.

A 2015 loan agreement between Belgian, German and Dutch development banks and Plantations et Huileries du Congo (PHC) owner at the time, Feronia Inc, the company which took over the former Unilever plantations — was recently made public in Delaware (USA) court filings. The agreement shows that the banks required PHC to hand back concessions over 60,000 ha of lands it was not using as a condition for the loan. They also required that PHC break up and re-title the remaining roughly 40,000 ha in small holdings to avoid a parliamentary approval for the renewal of the concessions as required under DRC law for large-scale concessions.

Needless to say, no concessions were handed back to the government and no land was returned to communities but the re-titling — and the loan itself — went ahead. None of this information was ever shared with the affected communities, who are now embroiled in a senseless mediation process. Worse, PHC now claims that the original land titles are still valid, while one of its owners is suing the others for using the company for money laundering. (More on this here)

On 4 April, an alliance of NGOs has demanded that the mediation process be suspended and that the banks’ complaints panel ensure that communities have access to the land documents and legal support to defend their interests.

The conflict actually goes back to the early 1900s, when Unilever’s co-founder set up massive plantations on 100,000 ha in what was then the Belgian Congo. (See here for the background.)